LLMs 31. LLMs: Inference

Quick Overview

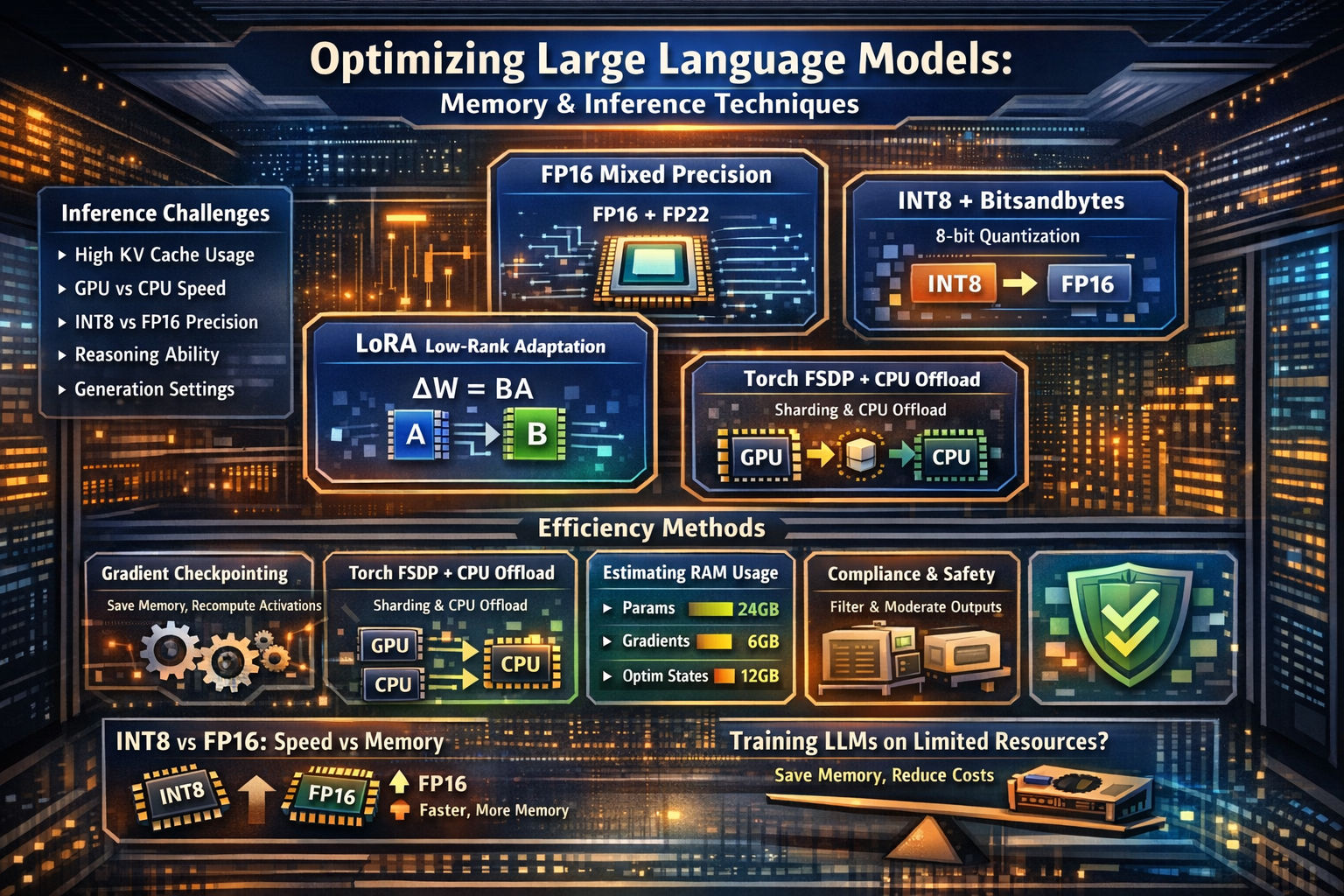

This technical guide covers large language model inference, memory and systems considerations, including KV-cache behavior, sequence-length and decoding strategy effects, memory/latency/cost trade-offs, and precision comparisons such as INT8 versus FP16 and GPU versus CPU performance.

Large Language Models (LLMs): Inference, Memory, and Practical Systems Thinking

This post is written as a learning-oriented resource, aimed at helping you understand not just what happens during large-model inference and training, but why these systems behave the way they do. The emphasis is on mental models that transfer across frameworks, hardware setups, and future model architectures.

Large Language Models: Inference

Inference is often treated as “the easy part” compared to training. In reality, inference at scale introduces its own set of bottlenecks—memory pressure, latency, and cost—that shape how modern LLM systems are built.

Understanding inference properly requires thinking in terms of sequence length, caching, precision, and decoding strategy, rather than just parameter count.

Why Does Large-Model Inference Consume So Much Memory and Never Seem to End?

Two mechanisms dominate memory usage during inference.

First, modern transformer models rely on key–value (KV) cache. As sequence length grows, every attention layer must store past keys and values so that new tokens can attend to all previous tokens. This cache grows linearly with sequence length and number of layers, and it is kept in GPU memory for speed.

Second, inference is autoregressive. Tokens are generated one at a time. Each new token triggers another forward pass that reuses the entire KV cache. Even though parameters are reused, the cached activations keep accumulating, making long-context inference feel like it “never ends.”

This explains why long prompts and chat histories are often the real memory killer—not model size alone.

How Fast Is Large-Model Inference on GPU vs CPU?

At the 7B-parameter scale, the difference is dramatic.

On CPUs, inference typically reaches around 10 tokens per second, even with optimized kernels. On GPUs, the same model benefits from massive parallelism in matrix multiplication and attention computation.

In practice, a single high-end GPU (for example, an A6000) can outperform multiple CPU sockets combined, often by an order of magnitude. The speed gap widens further as batch size or context length increases.

The takeaway is simple: CPUs can run LLMs, but GPUs are what make them usable.

During Inference, How Does INT8 Compare with FP16?

INT8 sounds like it should always be faster, but in practice it often isn’t—especially in common Hugging Face setups.

INT8 inference introduces:

- Extra dequantization steps

- Mixed-precision kernels

- More complex memory access patterns

As a result, INT8 inference is frequently slower than FP16, even though it uses less memory. INT8 shines when memory is the limiting factor, not raw throughput. If your model already fits comfortably in GPU memory, FP16 is often the better choice.

This is a recurring theme in systems design: lower precision saves memory, but not always time.

Do Large Models Have Reasoning Ability?

Large models do exhibit reasoning-like behavior, but it is important to be precise about what that means.

Two phenomena are especially relevant:

In-context correction: when a model makes a mistake, providing feedback can cause it to revise its answer within the same context window.

In-context learning: when given examples, rules, or structured hints, the model adapts its behavior without updating weights.

Both behaviors depend heavily on pattern matching from training data. The model is not reasoning symbolically; it is activating learned trajectories that resemble reasoning. Even when external knowledge is missing, the model can still produce plausible answers by extrapolating patterns and constraints introduced in the prompt.

This is why prompt design often feels like “teaching on the fly.”

How Should Generation Parameters Be Set?

Generation parameters control the shape of the output distribution, not just creativity.

In practice, tuning is empirical and task-dependent. A few guiding principles help:

- Temperature controls confidence. Lower values sharpen the distribution and reduce randomness. Extremely low values (e.g., 0.01) can approximate deterministic decoding.

- Top-p (nucleus sampling) controls diversity by limiting sampling to the most probable tokens that cover a given probability mass.

- Repetition penalty and no-repeat n-grams help suppress looping and degenerate outputs.

- Sampling (

do_sample=True) enables stochastic generation, which is often essential for creative or open-ended tasks.

These knobs do not make a model smarter—but they can make its behavior usable.

Memory-Efficient Methods for Training and Inference

LLMs push hardware to its limits. The key idea behind modern efficiency techniques is trading precision, recomputation, or communication for memory.

Even consumer GPUs (for example, an RTX 3090 with 24GB) can fine-tune multi-billion-parameter models when these methods are combined thoughtfully.

Estimating RAM Required for Training

Parameter count alone is misleading. True memory usage includes:

- Model parameters

- Gradients

- Optimizer states

- Activations

- CUDA runtime overhead

Using a 6B-parameter model as an example, precision changes everything. INT8 parameters require a quarter of the memory of FP32, but optimizer states and gradients still dominate total usage unless special care is taken.

Activation memory grows with:

- Hidden size

- Number of layers

- Context length

- Batch size

This is why reducing sequence length or using gradient checkpointing often has a larger impact than quantizing parameters.

FP16 Mixed Precision

Mixed-precision training uses FP16 for forward and backward passes, while keeping optimizer updates in FP32.

This approach:

- Cuts parameter and activation memory in half

- Preserves numerical stability

- Is widely supported in PyTorch and Hugging Face

For most workloads, FP16 is the first and safest optimization to apply.

INT8 + bitsandbytes

INT8 is extremely memory-efficient but inherently imprecise. The bitsandbytes library mitigates this through vector-wise quantization and mixed-precision decomposition, keeping sensitive components in higher precision.

The key insight is that not all weights are equally important. By isolating outliers and critical paths, INT8 can work surprisingly well, especially when paired with parameter-efficient fine-tuning.

LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation)

LoRA is one of the most impactful techniques for modern LLM fine-tuning.

Instead of updating full weight matrices, LoRA constrains updates to low-rank factors. Only a small number of parameters are trained, while the base model remains frozen.

This works because task-specific updates are often structured and low-dimensional. The same idea appears in recommendation systems, transfer learning, and control theory.

LoRA is not just a memory trick—it is an assumption about how learning happens.

Gradient Checkpointing

Gradient checkpointing saves memory by not storing activations during the forward pass. Instead, they are recomputed during backpropagation.

This introduces extra compute but can reduce activation memory dramatically. It is especially valuable for long-context models, where activations dominate memory usage.

Torch FSDP and CPU Offload

Fully Sharded Data Parallel (FSDP) shards parameters, gradients, and optimizer states across devices. CPU offloading extends this idea by temporarily moving tensors off the GPU during training.

This enables training models that would otherwise be impossible on limited hardware, at the cost of communication overhead and increased complexity.

In practice, partial sharding strategies are often more stable than fully aggressive ones.

Making Large-Model Outputs Compliant

Raw LLM outputs are not automatically safe or usable.

Production systems typically follow a pipeline:

- Generate candidate outputs

- Apply rule-based or classifier-based filters

- Accept, modify, or reject responses

- Fall back to safe templates when needed

This is less about censorship and more about system reliability.

Changes in Application Paradigms

LLMs shift application design.

Earlier systems relied on intent classification and rigid dialogue flows. LLMs reduce cold-start costs and improve flexibility but can become verbose or unfocused.

Hybrid systems are emerging:

- Small models handle routing, intent, and structure

- LLMs handle high-level reasoning and language generation

This division of labor improves controllability and business outcomes.

What If the Output Distribution Is Too Sparse?

When a model becomes overconfident, its output distribution collapses.

Common remedies include:

- Increasing temperature

- Adding regularization

- Penalizing repeated or dominant tokens

These techniques smooth the distribution and restore useful diversity.

Closing Thought

Large language models are not just algorithms—they are systems. Performance, cost, and reliability depend as much on precision choices, memory layout, and decoding strategies as on model architecture.

Once you see LLMs through this systems lens, techniques like INT8, LoRA, and FSDP stop feeling like hacks and start looking like design principles.

Comments (0)