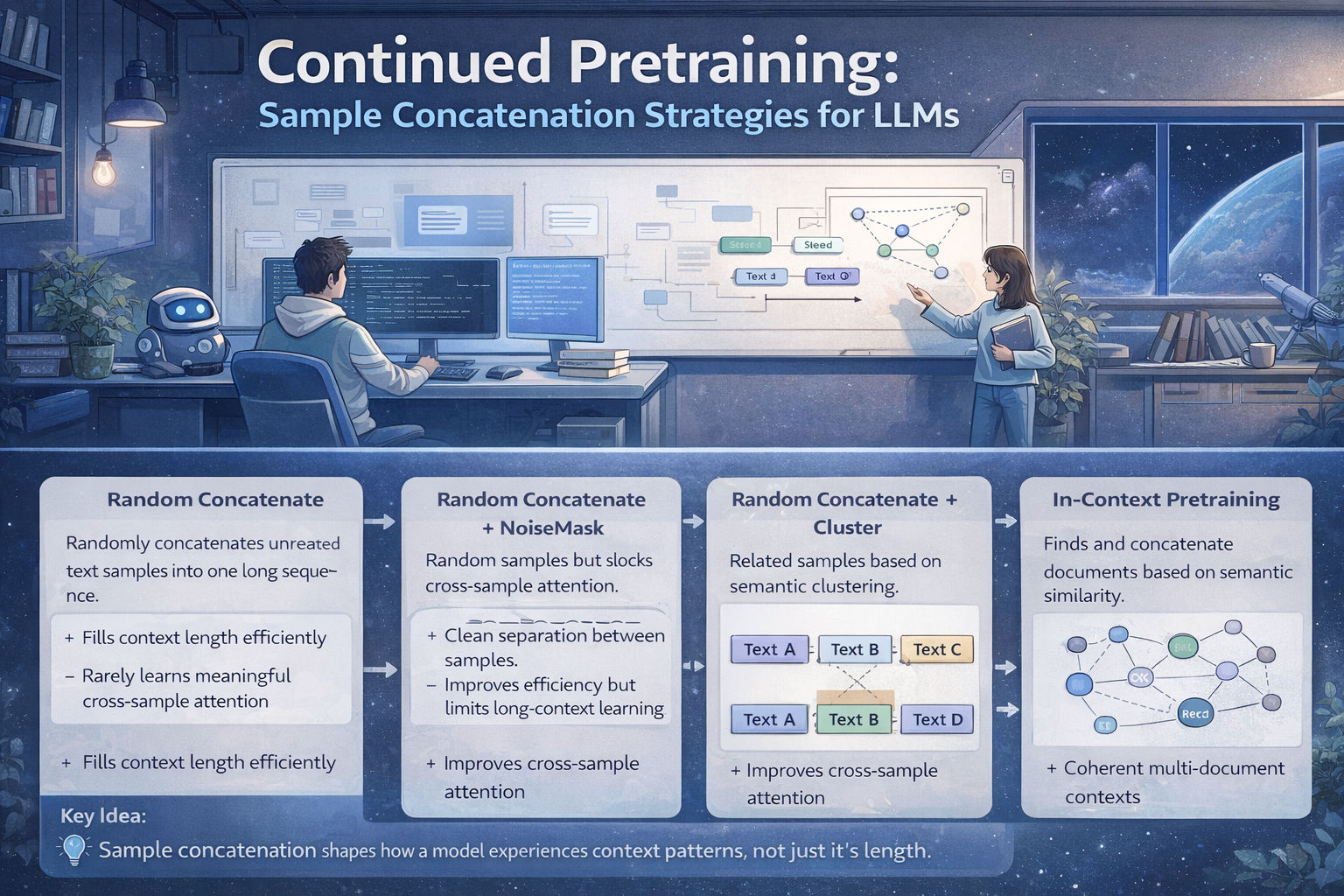

LLMs 33. Continued Pretraining (Pretrain): Sample Concatenation Strategies

Quick Overview

This technical guide examines sample concatenation strategies for continued pretraining of large language models, covering packing approaches, random concatenation, custom attention/noise masking, and their effects on long-context learning, in-context learning, and training efficiency.

Continued Pretraining: Sample Concatenation Strategies for Large Language Models

This learning post focuses on why sample concatenation exists in continued pretraining, how different strategies shape model behavior, and—most importantly—what these ideas teach us about long-context learning more broadly. Rather than treating concatenation as a data-engineering trick, we treat it as a signal-design problem: how we expose a model to structure, noise, and semantic continuity during pretraining.

I. Why Sample Concatenation Is Necessary in Pretraining

Modern LLMs are trained with very large maximum context lengths. If we feed one short document per training sample, most tokens in each sequence would be padding. This wastes computation and slows convergence.

Sample concatenation solves this by packing multiple text samples into a single sequence, allowing the model to fully utilize its context window. From a systems perspective, this is an efficiency optimization. From a learning perspective, it subtly shapes what kinds of dependencies the model is encouraged—or discouraged—to learn.

Concatenation therefore influences:

- how the model experiences long contexts,

- whether long-range attention is meaningful or noisy,

- and how much cross-document signal is present during training.

II. Random Concatenation: The Baseline Strategy

The most common strategy is random concatenation. Multiple unrelated text samples are randomly stitched together until the maximum sequence length is reached.

This approach is simple and surprisingly effective. It significantly reduces padding and exposes the model to long token streams. Even though the concatenated samples are usually unrelated, this does not catastrophically harm training.

Why? Because the learning signal in large-scale pretraining is largely contrastive at the distribution level, not dependent on logical continuity between neighboring samples. With enough diverse data, the model still learns robust local language patterns.

However, random concatenation has a clear limitation: the model rarely learns meaningful long-range dependencies. Attention across sample boundaries mostly becomes noise. This is acceptable for general language modeling, but suboptimal for tasks that require coherent long-context reasoning.

III. Random Concatenation with Noise Masking

To reduce interference between unrelated samples, one proposed improvement is to add a custom attention mask. The idea is to prevent tokens from attending across sample boundaries, so each example is processed independently even when concatenated.

This improves training stability and has been shown to boost in-context learning (ICL) performance in controlled experiments. By removing cross-sample noise, the model focuses more cleanly on each example.

However, this strategy introduces a deeper issue. With modern relative positional encodings such as RoPE or ALiBi, relative position information is already embedded in attention scores. Applying a hard attention mask removes all cross-example gradients after softmax.

As a result:

- the model never learns any cross-example interactions,

- long-context modeling capacity does not truly improve,

- the effective behavior becomes similar to reducing the context length.

In other words, masking improves efficiency but may hurt long-context generalization, which helps explain why many models degrade beyond their trained maximum context length.

IV. Random Concatenation with Semantic Clustering

A more balanced idea is to cluster samples by semantic similarity before concatenation. Instead of masking attention, we reduce noise by ensuring that concatenated samples are at least somewhat related.

This allows the model to:

- experience meaningful cross-document attention,

- learn broader semantic structures,

- and develop better long-context representations.

However, clustering introduces its own risks. If examples are too similar, the model may shift from learning patterns to memorizing content. This can lead to overfitting or data leakage, especially in narrow domains.

In practice, a middle ground works best: grouping samples by similarity while avoiding excessive redundancy. This is closely related to retrieval-style filtering used in in-context learning pipelines.

V. In-Context Pretraining: The Most Structured Approach

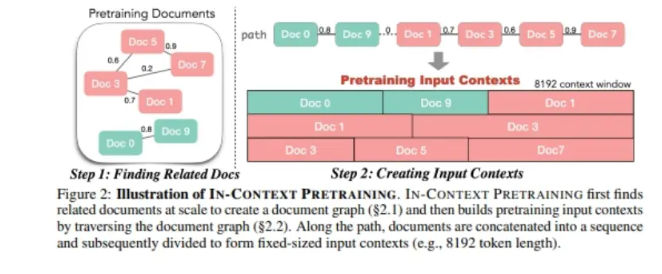

The most advanced strategy is In-Context Pretraining. Instead of random or loosely clustered concatenation, semantic similarity explicitly drives how contexts are constructed.

The typical workflow is:

- Embed all training samples using a dense retriever.

- Build a similarity graph based on cosine similarity.

- Starting from a seed example, traverse the graph to select related samples.

- Concatenate these samples into a long sequence.

- Split the sequence into fixed-length training chunks.

This approach exposes the model to coherent multi-document contexts during pretraining, closely resembling how it will later be used in retrieval-augmented generation or in-context learning.

Crucially, the authors emphasize that data volume still matters more than structure alone. Rich structure helps, but large and diverse datasets are what prevent overfitting and enable generalization.

VI. What These Strategies Teach Us Beyond Pretraining

Sample concatenation is not just about packing tokens—it is about designing the learning signal.

From these strategies, several transferable insights emerge:

- Long-context ability is learned, not automatic.

- Noise can sometimes help generalization, but uncontrolled noise limits reasoning.

- Hard constraints (like attention masks) improve efficiency but reduce expressive learning.

- Semantic structure helps only when paired with sufficient diversity.

- Distributional exposure matters more than perfect logical continuity.

These ideas generalize to:

- retrieval-augmented generation,

- in-context learning curriculum design,

- multi-document reasoning systems,

- and even non-NLP domains where sequence modeling matters.

Final Perspective

Continued pretraining is not just “more pretraining.” It is an opportunity to reshape how a model experiences context, structure, and noise.

Sample concatenation strategies sit at the intersection of data engineering, representation learning, and inductive bias design. Understanding them helps explain why some models scale gracefully to long contexts—and why others fail when pushed beyond their training regime.

Once viewed this way, concatenation stops being a preprocessing detail and becomes a core part of model behavior design.

Comments (0)