LLMs 38. Large Language Models (LLMs) Reinforcement Learning — PPO Section

Quick Overview

This guide covers Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) in LLM Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), detailing sampling, feedback and learning stages, reward modeling, common constraints like output collapse and reward exploitation, and connections to related methods such as DPO, ReST, and rejection sampling.

Large Language Models (LLMs) Reinforcement Learning — PPO in RLHF

A Conceptual Learning Guide to Sampling, Feedback, and Learning

This post focuses on PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) as used in LLM Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). Rather than treating PPO as a black-box algorithm, we’ll unpack why it is structured the way it is, how it fits naturally into language generation, and where its practical constraints come from. The goal is to help you build an intuitive mental model that transfers easily to related methods like DPO, ReST, and rejection sampling.

I. What Are the Main Steps of PPO in LLM RLHF?

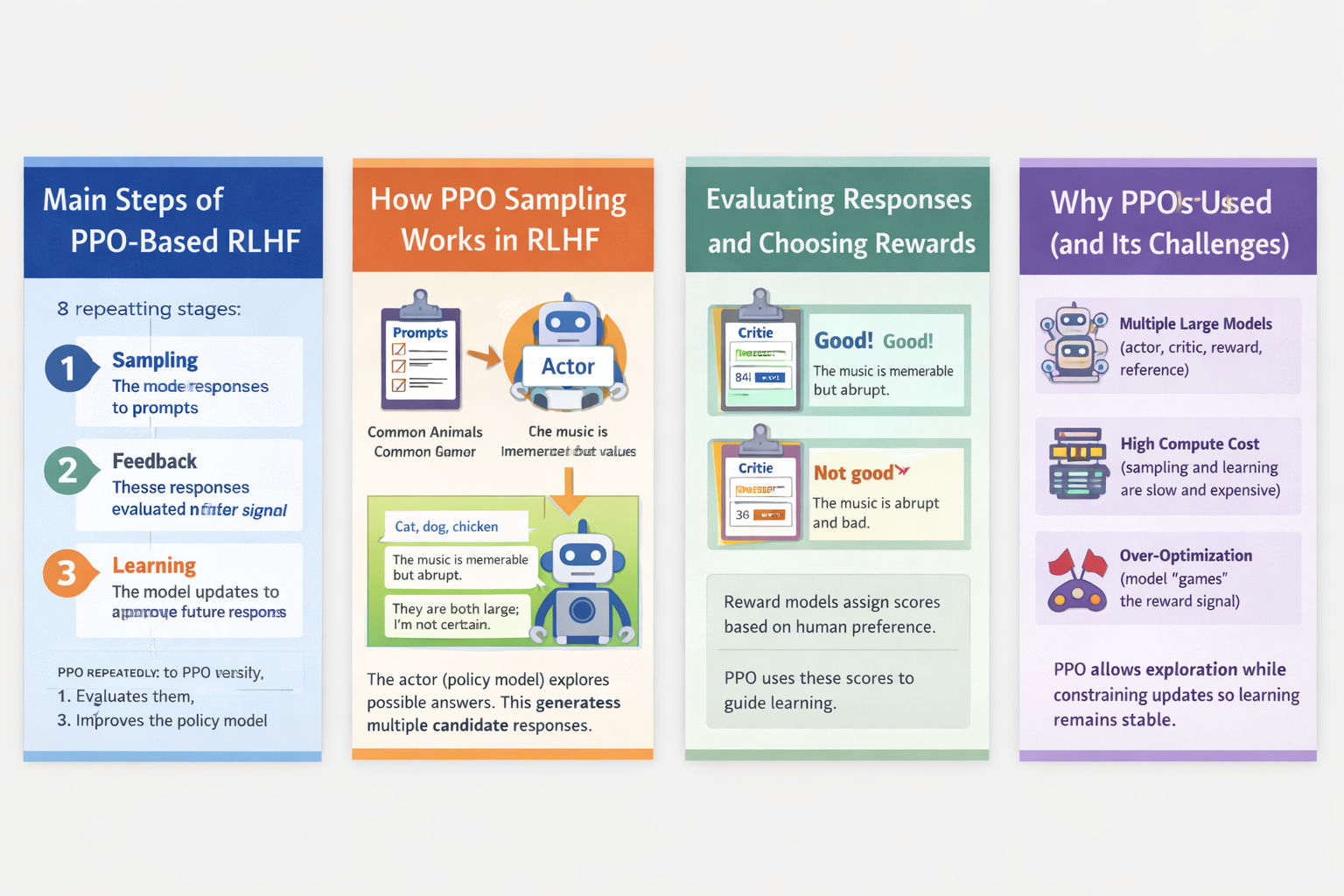

At a high level, PPO-based RLHF can be decomposed into three repeating stages:

- Sampling: the model generates responses to prompts

- Feedback: those responses are evaluated using a reward signal

- Learning: the model updates its parameters to improve future responses

In code-like form, the loop looks simple:

policy_model = load_model()

for step in range(20000):

prompts = sample_prompt()

responses = respond(policy_model, prompts)

rewards = reward_func(reward_model, responses)

for epoch in range(4):

policy_model = train(policy_model, prompts, responses, rewards)

PPO in LLM RLHF: Why It Works, Why It’s Hard, and Why It’s Being Replaced

This post focuses on one specific but critical part of RLHF: why PPO feels deceptively simple in structure yet extremely complex in practice. If you already understand the high-level RLHF pipeline, this piece is meant to deepen your intuition and help you transfer that understanding to newer alignment methods beyond PPO.

PPO Is Simple in Code, Complex in Constraints

At first glance, PPO in LLM RLHF looks almost trivial. The loop is straightforward: generate responses, score them, update the model, repeat. What makes PPO difficult is not what it does, but what it must avoid.

The model must improve without:

- collapsing its output diversity,

- drifting too far from human language,

- exploiting loopholes in the reward model,

- or optimizing proxy rewards at the expense of real quality.

Most of PPO’s machinery exists to enforce these constraints. In that sense, PPO is less about optimization speed and more about damage control.

An Intuitive Mental Model: Guided Trial-and-Error

LLM RLHF is best understood as guided trial-and-error learning rather than classical reinforcement learning.

A helpful analogy is a long-term teacher–student relationship.

The student—the language model—tries to answer questions. The teacher—human preference, approximated by a reward model—does not give perfect instructions, but instead reacts to outcomes. Good answers are encouraged. Poor answers are discouraged or corrected. Over time, the student internalizes what types of answers tend to be preferred.

Crucially, the student is not told exactly what to say. Unlike supervised learning, there is no single “correct” response. Exploration is required. This freedom to explore is what allows the model to move beyond imitation and adapt its behavior to subtle human preferences.

PPO Sampling: When the Model Becomes Its Own Data Generator

Sampling is the phase where RLHF fundamentally diverges from supervised fine-tuning.

Given a prompt, the model generates a response token by token. That response is treated as a trajectory—a sequence of decisions made under uncertainty. These trajectories are not labeled as correct or incorrect. They are simply attempts.

For example:

| Prompt | Response |

|---|---|

| “List three common animals.” | “Cat, dog, chicken.” |

| “How would you evaluate La La Land?” | “The music is memorable, but the ending feels abrupt.” |

| “Which is bigger, an elephant or a hippopotamus?” | “They are both large; I’m not certain.” |

At this stage, nothing is judged. The model is effectively writing its own training data, which is later evaluated.

This is the core conceptual shift:

in RLHF, the model is no longer a passive learner—it is an active participant in data generation.

Actor and Critic: Two Roles, One Brain

PPO relies on two tightly coupled components.

The actor is the language model we actually care about. Given a context, it produces a probability distribution over the next token. This is the model that will eventually be deployed.

The critic plays a quieter but essential role. It estimates how good the current situation is expected to be. In other words, it predicts future reward.

You can think of this as two cognitive processes:

- one decides what to say next,

- the other asks how well this is likely to go.

In practice, the critic is usually implemented as a value head attached to the same backbone as the actor. Its main purpose is not to judge quality directly, but to reduce variance and stabilize learning by providing a baseline.

Reward in LLM RLHF Is Global, Delayed, and Noisy

Unlike many reinforcement learning environments, LLM rewards are not immediate and not token-level.

The reward model evaluates the entire generated response and outputs a single scalar score. That score compresses many human preferences—helpfulness, correctness, tone, safety—into one number.

This scalar reward is then propagated backward through the sequence. PPO combines it with the critic’s value estimates to compute an advantage: how much better or worse the outcome was than expected.

On top of this, an explicit KL-divergence penalty is added. This term forces the updated model to stay close to the original SFT model, preventing it from drifting too far or learning to “game” the reward model.

This regularization is not optional. Without it, reward hacking and language degradation appear very quickly.

Why PPO Is Used—and Why It’s Becoming a Bottleneck

PPO became popular in RLHF because it strikes a workable compromise.

It allows exploration while keeping updates stable. It supports large neural policies. And empirically, it works well enough to align large models.

But the costs are substantial.

PPO-based RLHF typically requires:

- an actor model,

- a critic model,

- a reward model,

- and a reference model for KL regularization.

Sampling is slow. Training is expensive. Reward signals are imperfect proxies for real human judgment. And over-optimization often leads to worse real-world behavior despite higher reward scores.

These problems are not incidental—they are structural.

Why the Field Is Moving Away from PPO

Once you understand PPO’s role, the motivation behind newer methods becomes obvious.

Many recent approaches ask the same question from different angles:

Can we shape a model’s output distribution toward human preference without a heavy RL loop?

This leads to:

- rejection sampling instead of PPO,

- direct preference optimization instead of reward models,

- data-centric alignment instead of online reinforcement learning.

In this sense, PPO is not the destination—it is a stepping stone. It proved that alignment via preference optimization works, but it also revealed how costly that approach can be.

The Core Insight to Take Forward

PPO in LLM RLHF is not about teaching models new intelligence.

It is about reshaping behavior under constraints.

Sampling generates possibilities.

Feedback assigns value.

Constraints prevent collapse.

Once you see PPO through this lens, it becomes much easier to understand both its power—and why so many researchers are working to replace it.

Comments (0)