LLMs 45. Illustrated Guide to Distributed Training (I): Pipeline Parallelism

Quick Overview

This illustrated guide covers pipeline parallelism for distributed training, explaining why the technique exists, the memory-versus-utilization trade-offs, micro-batching, activation memory costs, and how the same system-design patterns generalize beyond LLMs.

Pipeline Parallelism: Learning to Think in Systems, Not Just GPUs

Pipeline Parallelism is often introduced as “splitting layers across GPUs,” but that description misses the deeper reason it exists. This learning post is designed to help candidates understand why pipeline parallelism matters, what problems it actually solves, and how the same thinking generalizes to other large-scale systems beyond Large Language Models (LLMs).

The goal is not to memorize GPipe diagrams or formulas, but to build intuition you can reuse in interviews, system design discussions, and real engineering work.

Why Pipeline Parallelism Exists at All

Large Language Models grow along three dimensions at once: depth, width, and data volume. When a model no longer fits on a single GPU, the first instinct is often to add more GPUs. But adding GPUs alone does not solve the problem unless work and memory are redistributed intelligently.

Pipeline Parallelism emerges from a simple constraint:

At some point, model depth becomes the limiting factor, not compute.

If layers cannot fit together on one device, they must be placed on different devices. This turns training into a staged process, where data flows through the model like items moving through an assembly line.

The Core Trade-Off: Memory vs. Utilization

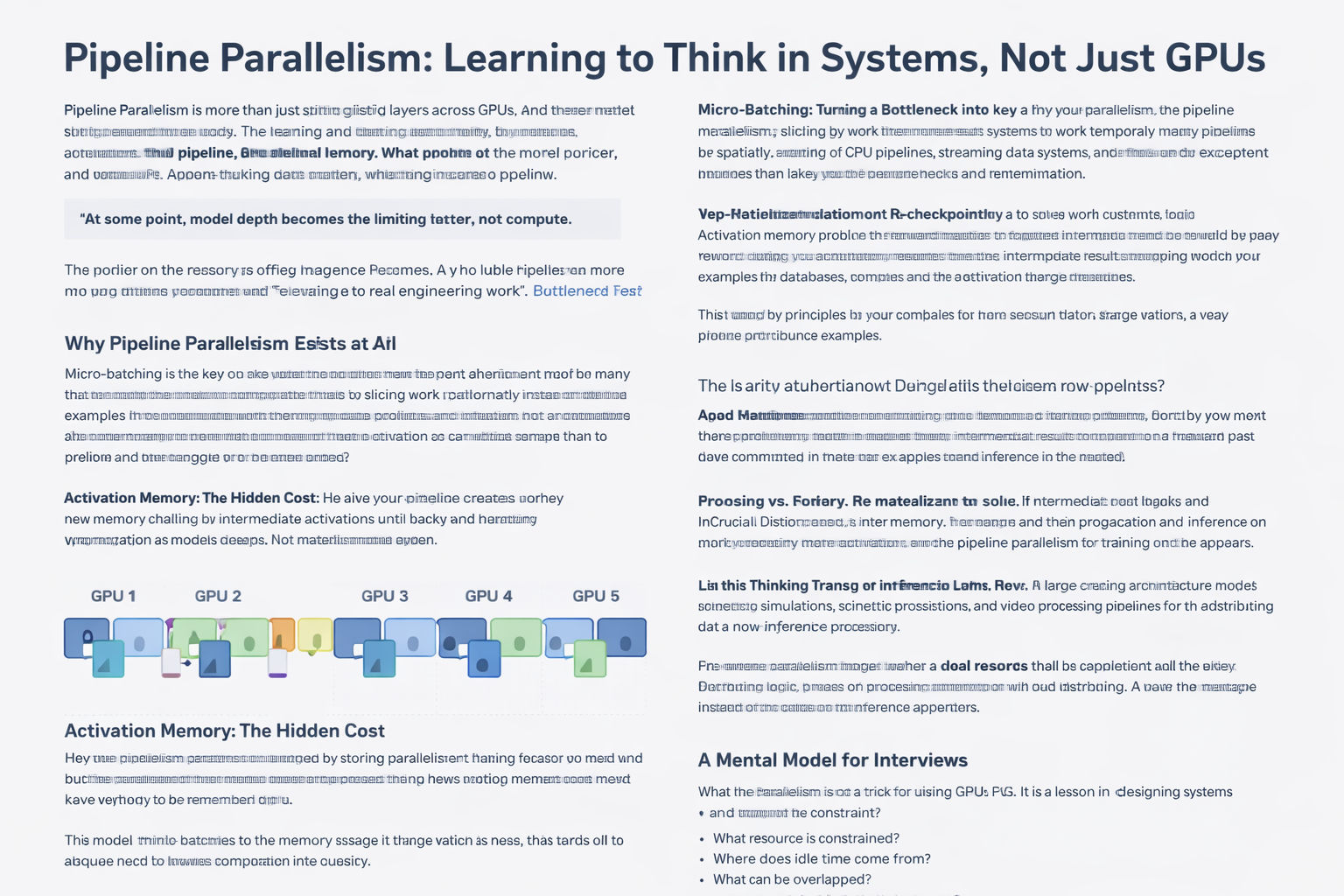

Naively splitting layers across GPUs solves the memory problem, but introduces a new one: idle time.

During training, forward computation flows from the first GPU to the last, and backward computation flows in reverse. Without careful scheduling, most GPUs spend significant time waiting. This idle time—often called pipeline bubbles—is the real enemy of pipeline parallelism.

This is a recurring systems lesson:

Solving one bottleneck often exposes another.

Understanding pipeline parallelism means understanding how engineers reduce idle time without increasing memory pressure.

Micro-Batching: Turning a Bottleneck into a Flow

Micro-batching is the key idea that makes pipeline parallelism practical. Instead of pushing a single large batch through the pipeline, the batch is split into many smaller micro-batches that enter the pipeline one after another.

This simple change has a profound effect. While one GPU processes micro-batch i, another GPU can already work on micro-batch i−1. Over time, the pipeline fills up and utilization increases dramatically.

What matters here is not the formula, but the pattern:

Increasing concurrency by slicing work temporally, not spatially.

You will see the same idea in CPU pipelines, streaming data systems, and distributed query engines.

Activation Memory: The Hidden Cost

Even with micro-batching, pipeline parallelism creates a new memory challenge. During training, intermediate activations must be stored until backward propagation completes. As models deepen, activation memory can rival or exceed parameter memory.

This is why pipeline parallelism alone is not enough for very large models.

The key insight is that not everything needs to be remembered.

Re-Materialization: Choosing What to Forget

Re-materialization—also known as activation checkpointing—solves the activation memory problem by deliberately forgetting intermediate results during the forward pass and recomputing them later during backward propagation.

This trades extra computation for lower memory usage. In large-scale systems, this trade-off is often favorable because compute scales more easily than memory.

This principle generalizes far beyond deep learning:

- Databases recompute instead of caching everything

- Compilers trade instruction count for register pressure

- Distributed systems recompute state instead of replicating it everywhere

The deeper lesson is learning when memory is more expensive than compute.

Why Pipeline Parallelism Works Especially Well for Transformers

Transformer-based models benefit more from pipeline parallelism than many vision models because:

- Layers are structurally similar

- Activation sizes are predictable

- Communication patterns are regular

This regularity allows pipeline stages to balance load more effectively, reducing idle time. In interviews, being able to explain why Transformers scale better than some other architectures is often more impressive than knowing exact speedup numbers.

Training vs. Inference: A Crucial Distinction

Pipeline parallelism is fundamentally a training-oriented strategy. Training can tolerate latency if throughput is high. Inference, on the other hand, is latency-sensitive and often cannot afford pipeline bubbles.

This distinction matters because strong candidates understand that:

A good training architecture is not automatically a good inference architecture.

Being able to explain this difference shows maturity in system-level thinking.

How This Thinking Transfers Beyond LLMs

Pipeline parallelism is not unique to Large Language Models. The same logic appears in:

- Large-scale recommendation models with deep towers

- Scientific simulations with staged computation

- Video processing pipelines

- Distributed data processing frameworks

Once you understand pipeline parallelism as flow control under resource constraints, you can recognize it everywhere.

A Mental Model for Interviews

When discussing pipeline parallelism, focus less on diagrams and more on reasoning:

- What resource is constrained?

- Where does idle time come from?

- What can be overlapped?

- What can be recomputed instead of stored?

Candidates who answer these questions clearly demonstrate systems intuition, not just framework familiarity.

Final Takeaway

Pipeline Parallelism is not a trick for using more GPUs.

It is a lesson in designing systems that stay busy under constraint.

If you can explain how micro-batching reduces bubbles, why re-materialization trades compute for memory, and when pipeline parallelism should not be used, you are thinking at the level expected of strong ML and AI systems engineers.

That mindset will carry far beyond any single model or framework.

Comments (0)