1.2 Define the Problem and Goal, Then Forming a Hypothesis

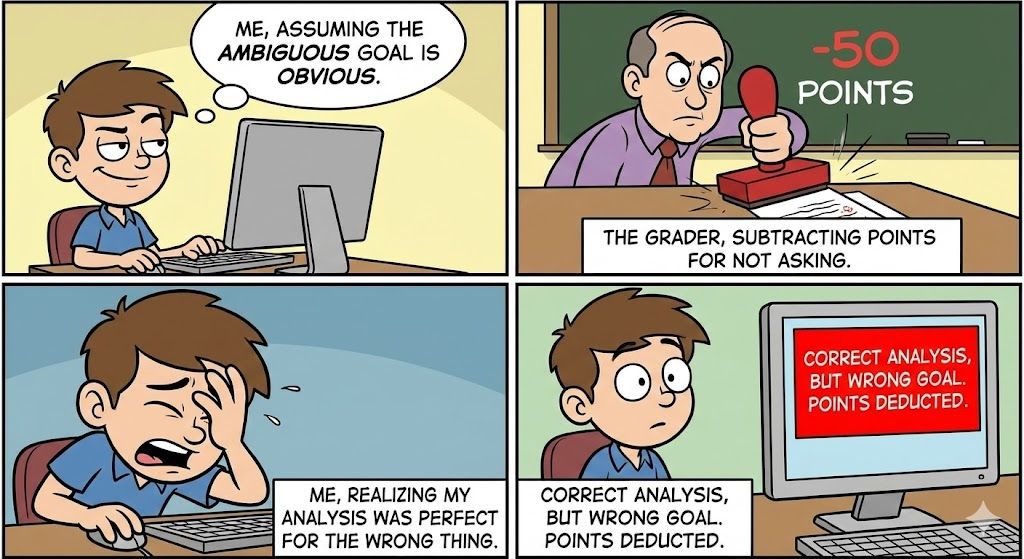

In real A/B testing interviews, defining the goal and forming the hypothesis are a single, inseparable reasoning step. The hypothesis you form is only as good as your understanding of the problem you are trying to solve. This is why asking clarifying questions is mandatory, not optional.

From an interviewer rubric perspective:

Failing to ask clarifying questions when the goal is ambiguous directly subtracts points, even if the later analysis is correct.

Candidates who jump straight into metrics or experiment design signal that they are optimizing blindly. From an interviewer’s perspective, that is a red flag. Products are built to solve specific problems, and experiments exist to validate whether a proposed change actually solves the intended problem.

Step 1: Clarify the Problem and the Goal (Before Anything Else)

The first thing a strong candidate does is pause and ask:

“What problem is this feature or experiment trying to solve, and why does the business want to build it?”

This step matters because a single product change can satisfy multiple, very different goals, each of which implies a different experiment design, metric choice, and interpretation.

Example: DoorDash Bike Dasher Option

If DoorDash introduces a bike option for Dashers, the goal is not self-evident. Reasonable goals could include:

Reducing costs / improving profitability

Bike Dashers may have lower operational costs than car-based Dashers.

Increasing Dasher supply (acquisition)

Users without vehicles can now register as Dashers.

Reducing delivery time

Bikes may navigate traffic more efficiently in dense urban areas.

Each of these represents a different problem statement, and therefore a different experiment. A strong candidate explicitly surfaces this ambiguity and asks the interviewer which objective the team cares about most.

Asking this question is not wasting time. It demonstrates product thinking, alignment, and seniority.

Common Goal Categories Interviewers Expect You to Reason About

While goals vary by company and product, most interview cases fall into a small number of recurring themes. These categories help structure your clarification discussion:

Acquisition — bringing in new users, suppliers, or creators

Activation — getting users to complete a meaningful first action

Retention — increasing repeat usage or long-term engagement

Revenue / profitability — increasing monetization or improving unit economics

Infrastructure / efficiency — reducing latency, cost, or system load

Volume growth — increasing orders, trips, messages, or content created

Deeper engagement — richer or more frequent user interactions

Quality of service — reducing complaints, defects, or failure rates

Marketplace or ecosystem balance — buyer vs seller outcomes, rider vs driver experience, creator vs consumer supply

Trust, safety, and risk reduction— reducing fraud, spam, abuse, chargebacks, or improving content safety

These are not boxes to tick. They are tools to reason about intent and ensure you and the interviewer are aligned before moving forward.

Step 2: Translate the Clarified Goal Into a Hypothesis

Once the goal is clarified, hypothesis formation becomes precise.

A hypothesis is not a fact. It is an assumption about a causal mechanism that you want to validate with an experiment.

Hypothesis = what we believe is true, but are not yet confident in.This is exactly why we need an A/B test.

DoorDash Example (Delivery Time Goal)

Suppose the interviewer clarifies that the goal is to reduce delivery time.

A strong hypothesis would be:

“By increasing Dasher supply and flexibility through bike deliveries, the system can assign orders more efficiently during traffic, leading to shorter delivery times.”

A senior candidate will also immediately consider what could go wrong:

Failure mode:

In suburban or rural areas, bike Dashers may increase delivery time due to longer distances and lower order density.

Acknowledging this is not a weakness. It shows that you understand experiments as risk-management tools, not validation rituals.

Meta Example: Stories and Retention

Consider a Meta product case where data shows that users who post Stories are more likely to return. The product idea is to prompt more users to create Stories.

If the clarified goal is retention, the hypothesis might be:

Encouraging users to post more Stories increases social interaction and feedback from friends, which in turn increases retention.”

However, this is still just an assumption. A strong candidate will immediately recognize a key risk:

What could go wrong:

Power users already inclined to post Stories may be driving the correlation, and prompting less engaged users may not increase interaction—or could even cause fatigue.

This distinction between correlation and causation is exactly why the experiment exists.

Why Hypothesis Quality Matters in Interviews

Hypothesis formation is where interviewers evaluate whether you truly understand causal inference.

A strong hypothesis:

Is explicitly tied to the clarified goal

Articulates a plausible causal mechanism

Makes it clear what belief the experiment is testing

Defines what success or failure would mean for the decision

If you cannot clearly state what assumption you are trying to validate, the experiment has no purpose.