1.3 A Framework for System Design Interviews

Why This Chapter Matters in Interviews

The biggest mistake candidates make in system design interviews is not having a framework. Without one, you either ramble through disconnected ideas or freeze when you do not know where to go next. A framework gives you a repeatable structure that works for any design problem.

This is not about being rigid or formulaic. It is about having a skeleton that keeps you organized so you can spend your brainpower on the actual design instead of figuring out what to talk about next.

Here is the reality: interviewers have seen hundreds of candidates. They can tell within the first 5 minutes whether someone has a structured approach. The candidate who says "Let me start by understanding the requirements" immediately signals competence. The candidate who starts drawing boxes on the whiteboard without asking a single question signals the opposite.

This chapter gives you that structure. Internalize it, practice it, and it will become second nature.

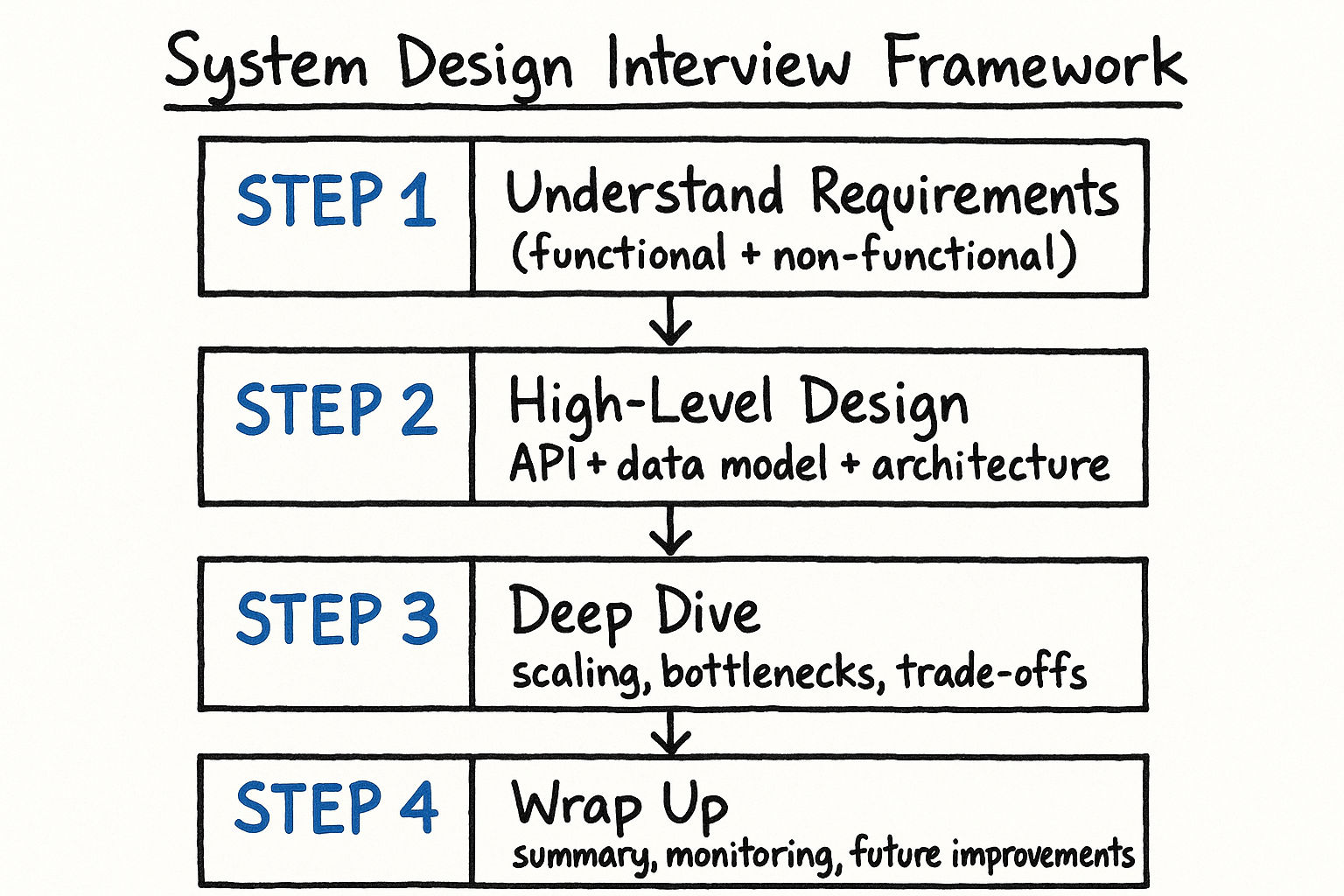

The 4-Step Framework

Every system design interview, regardless of the specific problem, can be structured into four phases. Budget your time roughly like this for a 45-minute interview:

| Step | What You Do | Time | % of Interview |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Understand the problem and establish design scope | Ask clarifying questions, define requirements | 3-10 min | ~15% |

| 2. Propose high-level design and get buy-in | Draw the architecture, walk through the main flow | 10-15 min | ~30% |

| 3. Design deep dive | Drill into 2-3 critical components | 10-25 min | ~40% |

| 4. Wrap up | Discuss bottlenecks, tradeoffs, and future improvements | 3-5 min | ~15% |

Time Management Strategy

Time management is one of the most underrated skills in system design interviews. Here is a practical approach:

The 5-minute check: At the 5-minute mark, you should be done with clarifying questions and starting to draw. If you are still asking questions, you are spending too long on Step 1.

The 15-minute check: By minute 15, you should have a complete high-level diagram and the interviewer should have agreed to the general approach. If you are still drawing the high-level design, you are behind.

The 35-minute check: By minute 35, you should be wrapping up your deep dives. If you are still going deep on your first component, you have spent too long and need to move to the wrap-up.

The 40-minute mark: Start wrapping up regardless of where you are. A clean ending with identified tradeoffs is much better than getting cut off mid-sentence.

Interview tip: Wear a watch or keep your phone face-up on the table. Glancing at the time is not rude — it shows you are organized and respectful of the time constraint.

What if you run out of time? This happens to everyone. If you feel time pressure, say: "I want to make sure we cover the most important aspects. Let me quickly sketch the data model for this component and then discuss the key tradeoffs." The interviewer will appreciate the awareness.

Step 1: Understand the Problem and Establish Design Scope

Do not start drawing boxes. Start by asking questions.

The interviewer deliberately gives you a vague prompt ("Design a chat system") because they want to see how you handle ambiguity. Jumping straight into the architecture signals that you make assumptions without validating them — a red flag in any engineering role.

What Questions to Ask

Organize your questions into three categories:

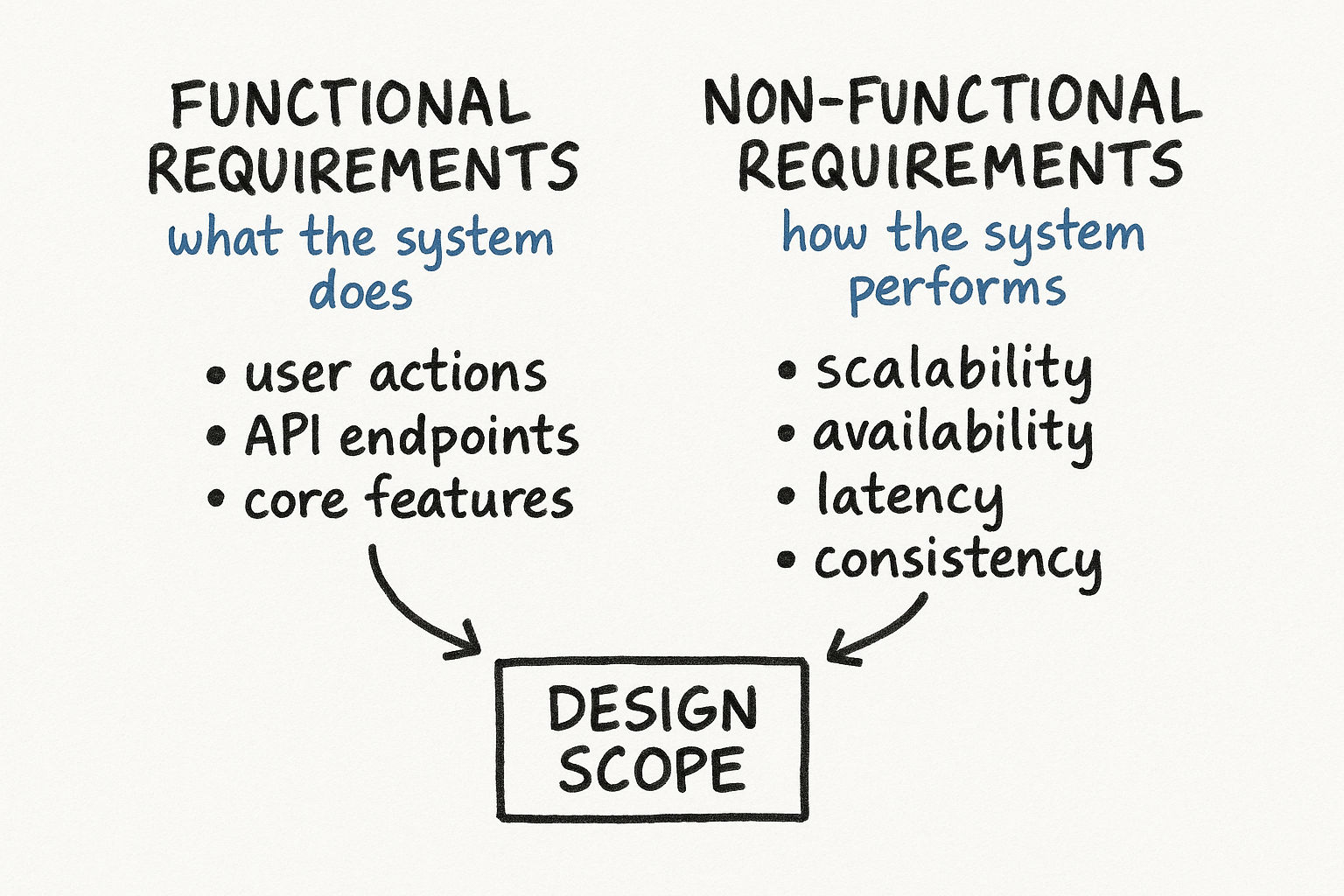

Functional requirements — what does the system do?

"What are the core features we need to support?"

"Who are the users? Are they consumers, businesses, or both?"

"What platforms do we need to support — web, mobile, or both?"

"Are there any features we should explicitly exclude to keep scope manageable?"

Non-functional requirements — how well does it need to work?

"How many users are we designing for? Thousands? Millions? Billions?"

"What are the latency requirements? Is this real-time or can we tolerate some delay?"

"What availability do we need? Three nines? Four nines?"

"Is consistency or availability more important? (CAP theorem tradeoff)"

"What are the read/write ratios?"

Constraints and assumptions:

"Can I assume we have existing services for authentication and payments?"

"Is there a preference for cloud provider or do we design cloud-agnostic?"

"What is the expected growth rate?"

Good vs. Bad Requirement Clarification

Here is what a strong clarification looks like versus a weak one for "Design a URL shortener":

Bad approach (too vague, no structure):

"So we need to shorten URLs... How many URLs? OK... And we need to redirect them. Anything else? OK, let me start designing."

This candidate asked a couple of questions but did not establish concrete requirements. The interviewer has no idea what the candidate plans to build.

Good approach (structured, specific, produces a contract):

"Let me make sure I understand the scope. For functional requirements: users submit a long URL and get back a short URL. When someone visits the short URL, they get redirected to the original. Do we need custom short URLs or just auto-generated? Do we need analytics — click counts, geographic data? Do we need an API or just a web interface?"

"For scale: how many new URLs per day? I will assume 100 million new URLs per day and a 10:1 read-to-write ratio, so 1 billion redirects per day. Does that sound reasonable?"

"For non-functional requirements: redirects should be fast — under 50ms. We need high availability since broken short URLs damage trust. URLs should never expire unless the user explicitly deletes them. We need the short URL to be as short as possible — 7-8 characters."

What makes this good: The candidate organized requirements clearly, proposed specific numbers for the interviewer to validate, and established a concrete scope. Now both the candidate and interviewer agree on what they are building.

How to Handle Push-Back

Sometimes the interviewer will push back on your assumptions or requirements. This is not a bad sign — it is the interviewer testing your adaptability.

Scenario: You say "I will assume 100 million DAU" and the interviewer responds "That seems high. Let us say 10 million DAU."

Good response: "Great, 10 million DAU changes things. At that scale, we probably do not need sharding yet, and a single database with read replicas should handle the load. Let me adjust my estimates."

Bad response: Arguing with the interviewer or getting flustered. Remember, the interviewer might be steering you toward a specific discussion point. Go with it.

Scenario: You ask about a feature and the interviewer says "What do you think?"

Good response: "I think for an MVP, we should exclude it because it adds complexity without affecting the core flow. But I will note it as a possible extension for the wrap-up discussion." This shows product sense and prioritization.

What you produce from Step 1: A clear list of functional and non-functional requirements. Write them down (or state them explicitly). This becomes your contract with the interviewer. If there is a disagreement later, you can point back to the requirements.

Interview tip: Spend no more than 5-8 minutes on this step for a 45-minute interview. Asking too many questions can signal indecisiveness. Once you have the core requirements, move to design. You can always ask additional questions as they come up naturally during the design.

Step 2: Propose High-Level Design and Get Buy-In

Now draw the architecture. At this stage, you are sketching the major components and how they connect — not diving into implementation details.

What to Include

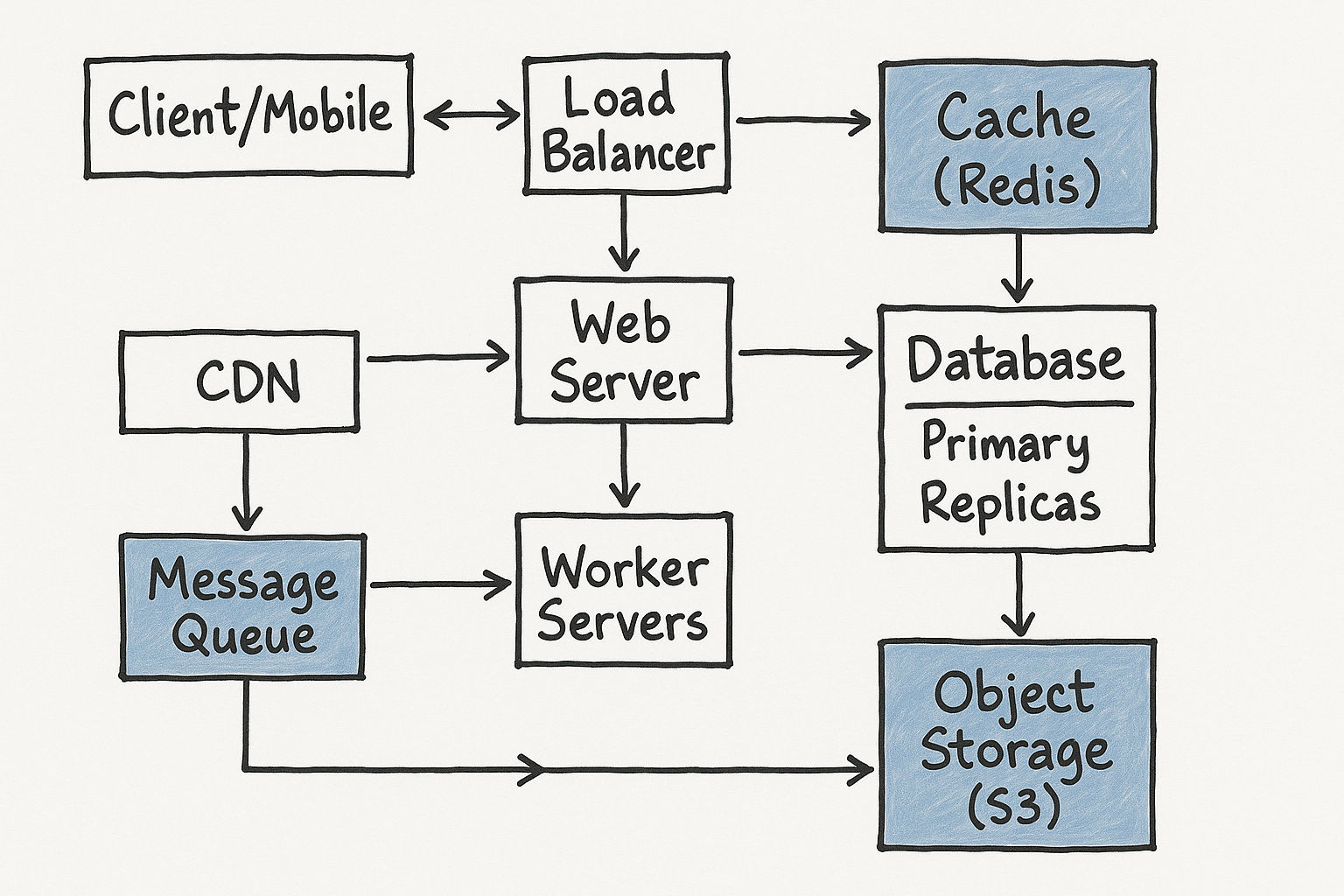

Your high-level diagram should have these elements:

Client (web/mobile) — the entry point for users

API layer — what endpoints exist and what do they do

Core services — the main business logic (keep it to 2-4 services max at this stage)

Data stores — which databases and why (SQL vs. NoSQL, what each stores)

Supporting infrastructure — CDN, cache, message queue, etc. (only what is clearly needed)

How to Present It

Walk through the main user flows, not the individual components. Components are boring in isolation — flows bring the architecture to life.

Bad approach (listing components):

"So we have a load balancer, then application servers, then a database, and a cache..."

This just describes boxes without explaining how they work together. The interviewer learns nothing about your design thinking.

Good approach (walking through a flow):

"Let me walk through the main user flow. A user opens the app and connects via WebSocket to the chat service. When they send a message, the chat service validates it, persists it to the messages database, and then looks up the recipient. If the recipient is online, the service pushes the message through their WebSocket connection in real time. If offline, the message is stored and a push notification is sent through our notification service. Let me draw this out..."

Here is a concrete example dialogue for designing a news feed:

"Starting from the top: the user opens the app and makes a GET request to /api/feed. This hits our load balancer, which routes to one of our feed service instances. The feed service first checks Redis for a precomputed feed. On cache hit, we return immediately — this is the fast path and should handle 95% of requests. On cache miss, the feed service queries the posts database to get recent posts from users this person follows, ranks them, caches the result, and returns it. For the write path, when a user creates a post, it goes through the post service, gets persisted to the database, and then we fan out the post to followers' cached feeds asynchronously through a message queue."

Getting Buy-In

At the end of this step, explicitly ask: "Does this high-level approach make sense, or would you like me to adjust anything before going deeper?"

This is not being timid — it is being collaborative. Interviewers appreciate it because it prevents you from spending 20 minutes going deep on the wrong thing.

What might happen at this point:

The interviewer says "Looks good, let us dive into the feed ranking" — great, you know where to focus

The interviewer says "I think you are missing something in the write path" — this is helpful, not critical. Adjust and continue.

The interviewer says "Why did you choose X over Y?" — this is a probe. Explain your reasoning clearly and mention the tradeoff.

Common High-Level Architecture Components

Here is a reference for the building blocks you will use across almost every design:

| Component | Purpose | When to Include |

|---|---|---|

| Load Balancer | Distributes traffic across servers | Almost always |

| API Gateway | Auth, rate limiting, routing | When you have multiple services |

| Application Servers | Stateless business logic | Always |

| Database (SQL) | Persistent structured data | Default choice |

| Database (NoSQL) | High-throughput or unstructured data | When SQL does not fit |

| Cache (Redis) | Hot data in memory | When reads dominate or latency matters |

| Message Queue | Async processing, decoupling | When you have background work |

| CDN | Static content delivery | When serving media or global users |

| Object Storage (S3) | Large binary files | When storing images, videos, files |

| Search Engine | Full-text search | When you need search functionality |

Interview tip: Do not include every component from this list in every design. Only add what your requirements demand. An interviewer will be suspicious if you add a message queue to a system that has no async processing needs. Every component should be justified.

Step 3: Design Deep Dive

This is where the interview is won or lost. You and the interviewer will pick 2-3 components to explore in detail. This phase takes up the bulk of the interview time, and it is where your technical depth shows.

How to Choose What to Dive Into

Sometimes the interviewer will tell you ("Let us talk about how you would handle message delivery"). Other times, you should propose it yourself. Here is how to choose:

Dive into components that are:

Most critical to the system's core functionality (the message delivery mechanism in a chat system)

Most technically challenging (the ranking algorithm in a news feed)

Most interesting from a scaling perspective (the notification fan-out for users with millions of followers)

Where the most interesting tradeoffs exist

Avoid diving into:

Standard infrastructure ("let me explain how a load balancer works" — the interviewer knows)

Authentication and authorization (unless the problem is specifically about security)

UI/frontend details (unless explicitly asked)

Here is how to propose a deep dive:

"I think the two most interesting components to explore are the message delivery mechanism and how we handle offline users. The message delivery involves real-time WebSocket connections, ordering guarantees, and at-least-once delivery — all of which have interesting tradeoffs. Should I start with message delivery?"

This shows the interviewer that you can identify what matters and that you are aware of the complexity involved.

What to Cover in Each Deep Dive

For each component you explore, address these four dimensions:

1. Data model: What does the schema look like? What are the access patterns?

"For our messages table, I would have message_id (UUID), channel_id, sender_id, content, created_at, and a status field for delivery tracking. The primary access pattern is fetching recent messages by channel_id, so channel_id should be the partition key. I would add a composite index on (channel_id, created_at) for efficient time-range queries."

2. API design: What endpoints or interfaces does this component expose?

"The chat service exposes three main interfaces: a WebSocket endpoint for real-time bidirectional messaging, a REST endpoint for loading message history (GET /api/channels/{id}/messages?before={timestamp}&limit=50), and an internal gRPC interface for the notification service to query online status."

3. Scaling strategy: How does this component handle 10x or 100x the current load?

"At 10x load, we would shard the messages database by channel_id using consistent hashing. WebSocket connections would be distributed across multiple servers, with a Redis pub/sub layer for cross-server message routing. At 100x, we would need to move to a write-optimized database like Cassandra for the message store and implement connection pooling at the WebSocket layer."

4. Failure modes: What happens when this component fails? How do you recover?

"If a WebSocket server crashes, all clients connected to it will reconnect (clients should have automatic reconnection with exponential backoff). When they reconnect, they send their last-received message_id, and the new server fetches any missed messages from the database. We might deliver some messages twice, so the client deduplicates using message_id."

Example Deep Dive: Message Delivery in a Chat System

Here is a complete deep dive example to illustrate the depth interviewers expect:

Data model:

Messages table: message_id, channel_id, sender_id, content, created_at. Partitioned by channel_id for locality.

Channel members table: channel_id, user_id, last_read_message_id (for read receipts).

Delivery mechanism:

WebSocket connections for real-time delivery. Each user maintains one persistent WebSocket connection.

If recipient is online: push message through their WebSocket connection immediately.

If recipient is offline: store message in the database and send a push notification via APNs/FCM.

For group messages: iterate through all channel members and deliver to each (fan-out on write for small groups, fan-out on read for very large groups).

Message ordering:

Use a monotonically increasing sequence number per channel, not wall-clock time. Wall-clock time can drift across servers, leading to messages appearing out of order.

The sequence is generated by the database (e.g., PostgreSQL SEQUENCE or an atomic counter in Redis).

Delivery guarantees:

At-least-once delivery: the server sends the message and waits for a client acknowledgment. If no ACK within 5 seconds, retry.

The client deduplicates using message_id (idempotent processing on the client side).

We choose at-least-once over exactly-once because exactly-once is much harder and a duplicate message is less harmful than a lost message.

Here is how you would walk through this:

"When User A sends a message to User B, the message hits our chat service through A's WebSocket connection. The service assigns a sequence number within the channel, persists the message to the database, and immediately looks up B's connection state. If B is connected to this same server, we push directly. If B is connected to a different chat server, we publish to a Redis pub/sub channel that the other server subscribes to. If B is offline, we persist the message and trigger a push notification. When B comes online later, the client sends its last-received sequence number, and we fetch all messages with a higher sequence number."

Strategies for Which Components to Deep Dive

If you are unsure what the interviewer wants to explore, here are good defaults based on system type:

| System Type | Good Deep Dive Topics |

|---|---|

| Messaging/Chat | Message delivery, ordering, offline handling |

| Social Feed | Feed generation (fan-out), ranking algorithm |

| URL Shortener | Hash generation, collision handling, redirect performance |

| Rate Limiter | Algorithm choice (token bucket vs sliding window), distributed rate limiting |

| Notification System | Delivery channels, priority/throttling, template engine |

| Search Engine | Indexing pipeline, ranking, query parsing |

| Video Streaming | Encoding pipeline, adaptive bitrate, CDN strategy |

| E-commerce | Inventory management, payment processing, order state machine |

Step 4: Wrap Up

Use the last few minutes productively. Do not just trail off — a strong ending can elevate your entire interview.

Strong Wrap-Up Moves

1. Identify bottlenecks: "The main bottleneck in this design is the single message database primary. Under extreme write load, we would need to shard by channel_id. I would also watch the WebSocket servers — each can handle about 100K concurrent connections, so at 10 million concurrent users, we need at least 100 servers in the WebSocket tier."

2. Discuss tradeoffs you made: "I chose eventual consistency for the online status feature because strong consistency would require coordination across all WebSocket servers for every status change. For a non-critical feature like online indicators, showing a slightly stale status is acceptable. If it were message delivery, I would not make the same tradeoff."

3. Suggest improvements with priority: "If we had more time, the highest-priority additions would be: first, message search using Elasticsearch with an async indexing pipeline; second, read receipts stored per-user in the channel members table; third, message editing and deletion with tombstone records. I would prioritize search because it is the most requested feature in messaging apps."

4. Mention operational concerns: "We should add monitoring on WebSocket connection counts and message delivery latency. If delivery latency exceeds 1 second, we should alert. We should also track the ratio of online-to-offline deliveries — if it shifts significantly, our push notification costs might spike."

5. Discuss error handling: "For error handling, I would implement a dead letter queue for messages that fail delivery after 3 retries. We would have an operations dashboard showing failed messages, and an automated recovery process that retries dead-lettered messages every hour."

What interviewers love: Self-awareness about the limitations of your design. Nobody expects a perfect architecture in 45 minutes. They want to see that you know where the weak points are.

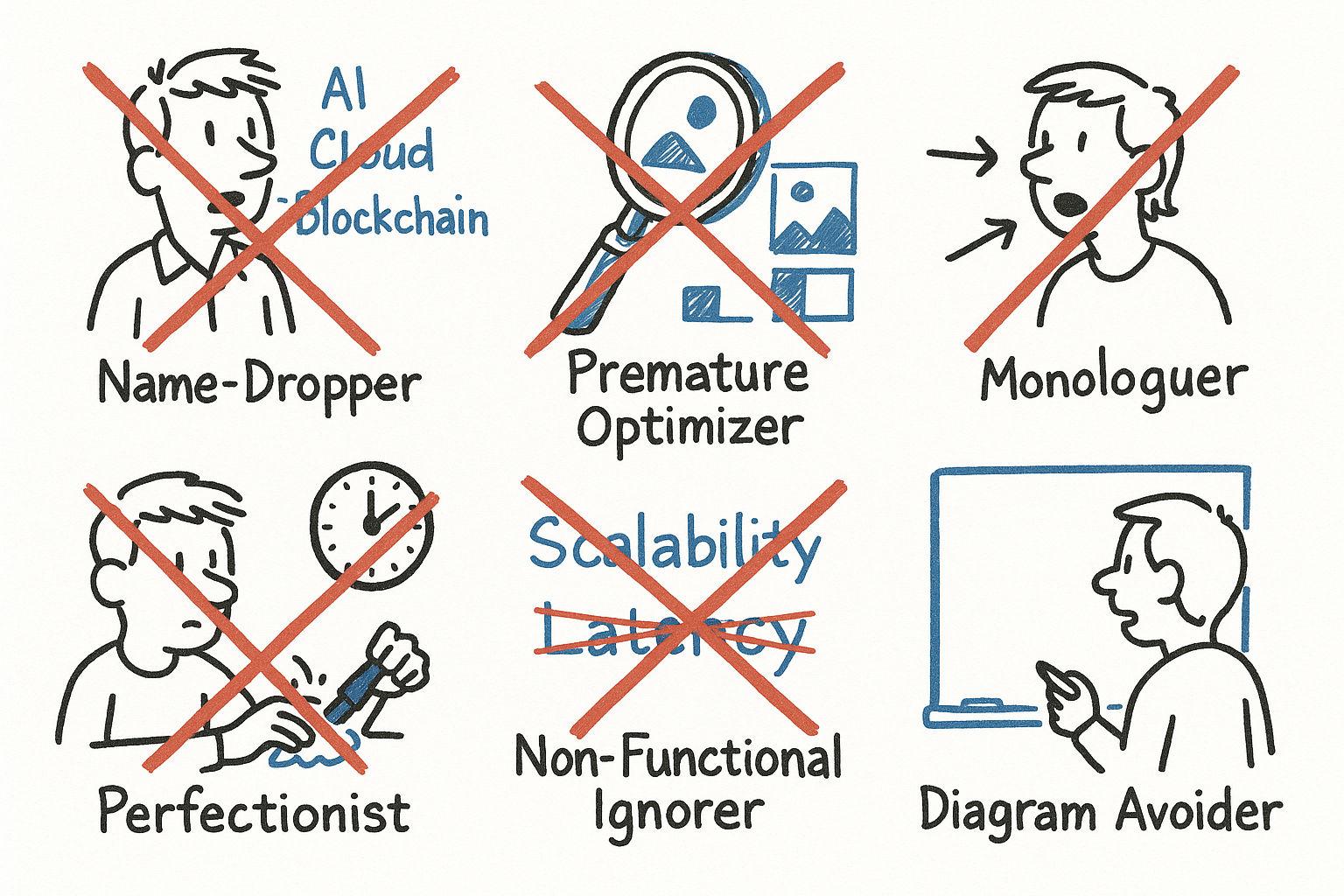

Common Anti-Patterns in System Design Interviews

Knowing what NOT to do is just as important as knowing what to do. Here are the most common mistakes and how to avoid them:

Anti-Pattern 1: The Technology Name-Dropper

What it looks like: "We will use Kafka for messaging, Cassandra for storage, Elasticsearch for search, Redis for caching, Kubernetes for orchestration, and Terraform for infrastructure..."

Why it is bad: Listing technologies without explaining WHY you chose them signals that you are regurgitating buzzwords, not engineering a solution.

Fix: For every technology you mention, add one sentence of justification. "I would use Kafka here because we need a durable, high-throughput message bus that supports replaying events — RabbitMQ would work for the queuing part but does not give us event replay."

Anti-Pattern 2: The Premature Optimizer

What it looks like: Starting with sharding, multi-region deployment, and microservices before establishing that the system even needs them.

Why it is bad: Over-engineering for scale you do not need shows poor judgment. If the interviewer says the system has 10,000 users, designing for 10 billion is a red flag.

Fix: Start simple and explicitly state when you would evolve the architecture. "At 10,000 users, a single server handles this fine. If we grow to 1 million, I would add a load balancer and read replicas. At 10 million, we would need caching and potentially sharding."

Anti-Pattern 3: The Monologuer

What it looks like: Talking for 10-15 minutes straight without checking in with the interviewer.

Why it is bad: The interview is supposed to be a conversation, not a presentation. If you monologue, you might be going deep on something the interviewer does not care about, while missing what they actually want to discuss.

Fix: Pause every 3-5 minutes and check in. "Does this level of detail make sense for the feed generation, or would you like me to move on to the storage layer?" Read the interviewer's body language. If they look bored, switch topics.

Anti-Pattern 4: The Perfectionist

What it looks like: Getting stuck on one component trying to make it perfect, running out of time, and never covering the rest of the system.

Why it is bad: A system design interview is about breadth AND depth. Spending 30 minutes on the database schema while never discussing caching, scaling, or fault tolerance is a failure even if the schema is perfect.

Fix: Set internal time limits. Spend at most 10 minutes on any single deep dive. If you are not done, say "There is more to explore here, but let me cover the other critical components first and we can come back if time allows."

Anti-Pattern 5: The Non-Functional Ignorer

What it looks like: Designing a system that handles the happy path perfectly but never mentioning latency, availability, consistency, or failure handling.

Why it is bad: Real systems fail. Real systems have latency constraints. Ignoring non-functional requirements suggests you have not built or operated real systems.

Fix: Throughout your design, weave in non-functional considerations. When you add a database: "What happens when it goes down?" When you add a cache: "What is our consistency guarantee?" When you add an API: "What is the expected latency?"

Anti-Pattern 6: The Diagram Avoider

What it looks like: Describing the architecture purely in words without drawing anything.

Why it is bad: Visual diagrams make complex systems understandable. Without a diagram, the interviewer has to build a mental model from your words alone, which is much harder.

Fix: Draw early and reference your diagram throughout. Point to specific components as you discuss them. Update the diagram as the design evolves.

How to Handle Specific Difficult Moments

When You Do Not Know Something

Bad: Making something up or giving a vague non-answer.

Good: "I am not deeply familiar with the internals of Cassandra's consistency model, but I know it offers tunable consistency — you can configure it per query from eventual to strong. For this use case, I would configure it for quorum reads and writes, which gives us a good balance. I would want to research the specific configuration before implementing."

Honesty with a reasonable approximation is much better than confident nonsense.

When the Interviewer Disagrees

Bad: Arguing or getting defensive.

Good: "That is a good point. If we are worried about the write amplification from my fan-out-on-write approach, we could switch to fan-out-on-read for users with more than 10,000 followers. That is actually how Twitter handles this — the hybrid approach gives us the best of both worlds. Let me update the diagram."

Show that you can incorporate feedback and adapt your design. This is a collaboration.

When You Realize Your Design Has a Flaw

Bad: Ignoring it and hoping the interviewer does not notice.

Good: "Actually, I just realized there is a problem with this approach. If two users send messages simultaneously, we could get a race condition on the sequence number. Let me fix that — we should use a database sequence or an atomic counter in Redis instead of generating the sequence in the application layer."

Self-correcting shows strong engineering instincts.

When You Are Asked Something Completely Unexpected

Bad: Panicking or saying "I do not know."

Good: "I have not thought about that specific aspect before. Let me reason through it..." Then apply first principles. Break the problem down into smaller parts. Make reasonable assumptions. The interviewer is testing your problem-solving ability, not your memorization.

Dos and Don'ts Summary

Do:

Ask clarifying questions before designing

Start with the simplest design that meets the requirements, then scale

Communicate your thought process out loud — the interviewer cannot read your mind

Make explicit tradeoffs and explain why ("I chose X over Y because...")

Draw diagrams and reference them while talking

Check in with the interviewer every 3-5 minutes

Mention monitoring and error handling

Connect your back-of-the-envelope numbers to design decisions

Acknowledge uncertainty honestly

Don't:

Jump into the deep dive without establishing the high-level design first

Over-engineer for scale you do not need

Spend too long on one component and run out of time

Give a monologue — this should be a conversation

Name-drop technologies without explaining why you chose them

Ignore non-functional requirements (latency, availability, consistency)

Get defensive when the interviewer pushes back

Forget to wrap up — always leave 3-5 minutes for the summary

A Complete Example: Applying the Framework

To make the framework concrete, here is how the first few minutes of a "Design a notification system" interview might go using this framework:

Step 1 (minutes 0-5):

"Before I start designing, let me clarify a few things. What types of notifications are we supporting — push notifications, SMS, email, or in-app? ... OK, all four. How many users? 100 million DAU. What is the expected volume — are most users getting a few notifications per day or hundreds? ... About 10 per user per day, so roughly 1 billion notifications per day, which is about 12,000 per second, with peak maybe 3x that at 36,000/second."

"For non-functional requirements: what is the latency requirement? Should notifications be real-time or is a few minutes delay acceptable? ... Under 30 seconds for push, email within 5 minutes. Is ordering important? ... Nice to have but not critical. Do we need delivery confirmation? ... Yes, we need to track whether each notification was delivered and read."

Step 2 (minutes 5-15):

"Let me draw the high-level architecture. We have a notification service that receives notification requests from other services via an internal API. It validates the request, applies user preferences (do not send email to users who opted out), and then routes to the appropriate channel — push, SMS, email, or in-app. Each channel has its own queue because they have different throughput characteristics and failure modes. Workers consume from each queue and call the respective third-party APIs — APNs for iOS push, FCM for Android, Twilio for SMS, SendGrid for email. Delivery status callbacks update our delivery tracking database. Does this approach make sense?"

Step 3 would dive into the priority/throttling system, the preference service, or the delivery tracking mechanism — depending on what the interviewer finds most interesting.

How This Framework Connects to the Rest of the Course

Every chapter that follows uses this exact 4-step structure. When you read "Design a Rate Limiter" or "Design a Live Streaming Platform," the approach is always:

Clarify requirements and scope

Propose high-level design

Deep dive into critical components

Discuss tradeoffs and improvements

Practice with the framework on the chapters ahead. By the time you have worked through several designs, the structure will be second nature — and you can focus entirely on the substance of each specific problem.

The framework is your safety net. Even on a question you have never seen before, you will know exactly how to start, how to organize your thoughts, and how to manage your time. That confidence alone puts you ahead of most candidates.