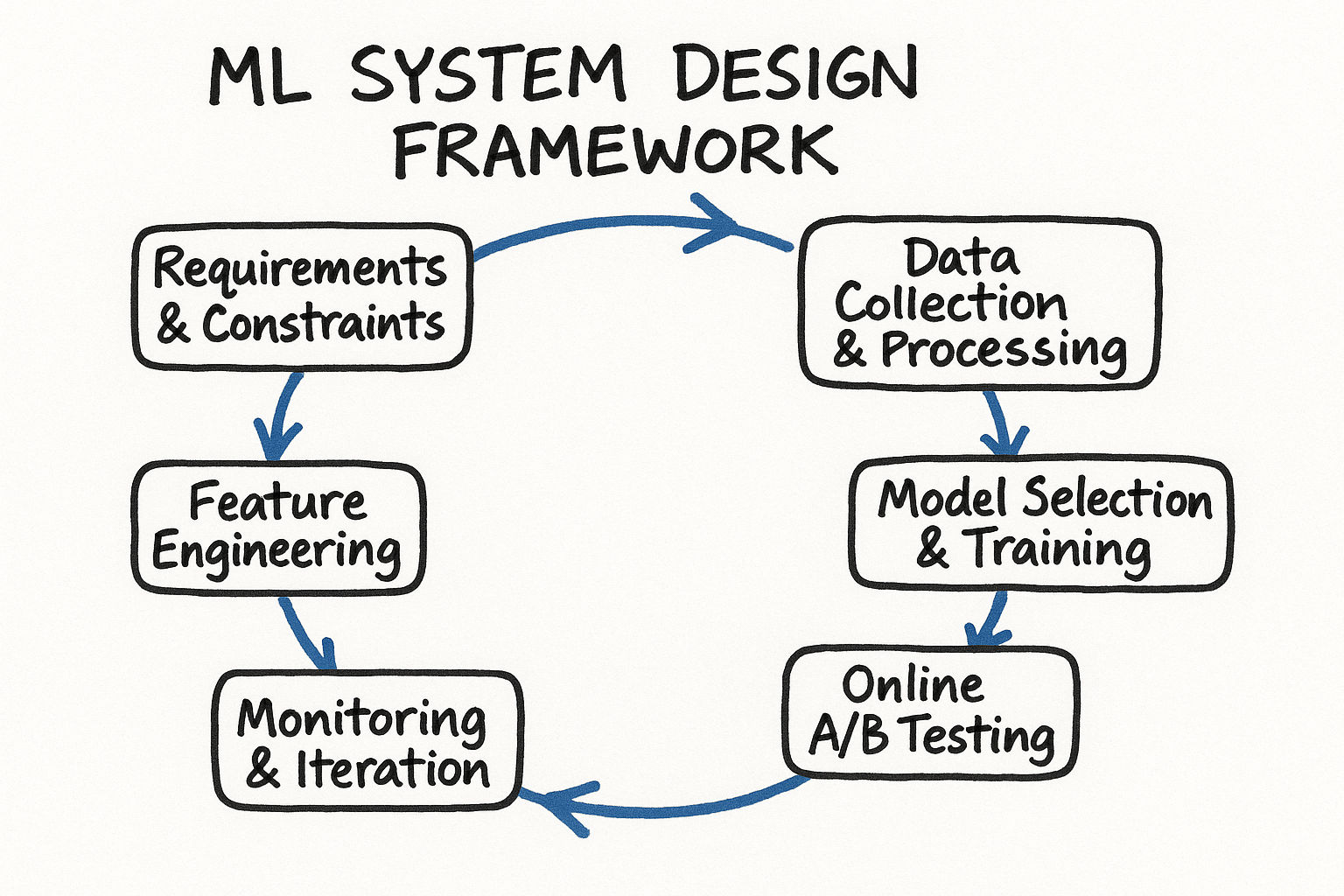

1.2 A Framework for ML System Design: From Requirements to Deployment

A Framework for ML System Design

This is the most important lesson in the entire course. Everything else builds on this framework.

When you walk into an ML system design interview, you need a structured approach that works for any problem -- whether it is design a spam detector or design a video recommendation system. Without a framework, you will ramble. With one, you will sound like someone who has done this before.

Here are the 12 steps. Memorize the structure, but internalize the reasoning behind each step.

Step 1: Clarify Requirements

Before you design anything, you need to understand what you are building. This is where most candidates mess up -- they start solving before they understand the problem.

Functional Requirements

What should the system actually do? Ask questions like:

What is the user-facing product? (mobile app, web, API, internal tool)

Who are the users? (consumers, businesses, internal teams)

What action does the ML model need to support? (rank items, classify content, generate text)

What is the expected input and output from the user perspective?

Non-Functional Requirements

These shape your entire architecture:

Scale: How many users? How many predictions per second?

Latency: Does the prediction need to happen in real time (under 100ms) or is batch processing OK?

Freshness: How fresh does the data need to be? Real-time features or daily aggregates?

Accuracy vs. speed trade-off: Is it better to be slightly less accurate but much faster?

Fairness and bias: Are there specific fairness constraints?

What Are We Optimizing?

This is the most important question you can ask: what does success look like? Get the interviewer to tell you (or propose) a business metric. Examples:

Increase user engagement (time spent, clicks, shares)

Reduce fraud losses (dollar amount of fraud prevented)

Improve relevance (user satisfaction scores)

Example Dialogue: Clarifying a Content Moderation System

Here is how a strong candidate navigates the clarification phase for a content moderation problem:

Candidate: Before I start designing, I want to understand the scope. When you say content moderation, what types of violations are we focused on? Hate speech, violence, nudity, spam, misinformation -- or all of the above?

Interviewer: Let us focus on hate speech and violence for now.

Candidate: Got it. And what content types are we moderating -- text posts, images, videos, or all three?

Interviewer: Start with text, but think about how you would extend to images.

Candidate: Makes sense. What is our latency requirement? Do we need to classify content before it is shown to any user, or can we allow some content to be visible initially and then take it down after review?

Interviewer: We want to catch most violations before they are shown, but a small delay of a few seconds is acceptable for borderline cases.

Candidate: That helps a lot. And roughly what scale are we talking about? How many posts per day?

Interviewer: About 500 million posts per day.

Candidate: OK, so we need roughly 6,000 classifications per second at steady state, with peaks probably 2-3x that. And one more question -- what is more important here, minimizing harmful content that slips through (recall) or minimizing legitimate content that gets incorrectly removed (precision)?

Interviewer: Recall is more important, but we cannot have too many false positives because that hurts user trust and engagement.

Notice how each question shapes the design decisions that follow. The latency requirement tells you whether you need real-time inference. The scale tells you about infrastructure needs. The precision-recall preference tells you how to tune your model and set thresholds.

Interview tip: Spend 5-8 minutes on clarification. It feels like a lot, but it is the highest-ROI time in the interview. A well-scoped problem is 10x easier to solve than a vague one.

Step 2: Frame as an ML Problem

Not every problem needs ML. Before diving into models, ask yourself: is ML actually the right approach here?

ML is appropriate when:

The problem has patterns in data that are hard to express with rules

You have (or can get) sufficient labeled data

The problem requires personalization at scale

Rules-based approaches would be too brittle or too many to maintain

ML is NOT appropriate when:

Simple rules or heuristics work well enough

You have very little data

The problem requires perfect accuracy with zero tolerance for error

A lookup table or deterministic algorithm solves it

If ML is appropriate, frame the problem as a specific ML task:

| ML Task | Example | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Binary classification | Spam vs. not spam | Two clear outcomes, need a yes/no decision |

| Multi-class classification | Categorize support tickets | Multiple distinct categories, one label per input |

| Multi-label classification | Tag content with topics | Multiple labels can apply simultaneously |

| Ranking / Learning to rank | News feed ordering | Need to order items by relevance or quality |

| Regression | Predict delivery time | Continuous numerical output |

| Retrieval + Ranking | Search results, recommendations | Large candidate pool needs narrowing then ordering |

| Sequence modeling | Next word prediction | Sequential or temporal patterns matter |

| Anomaly detection | Fraud detection | Rare events need to be flagged from normal behavior |

| Clustering | User segmentation | Discover natural groupings without labels |

Follow-Up Questions Interviewers Might Ask

Why did you choose classification over regression here? Be ready to explain. For example, for fraud detection you might say: We could frame this as regression (predicting fraud probability) or binary classification (fraud vs. not fraud). I prefer binary classification because our downstream action is binary -- we either block the transaction or allow it. The probability score from the classifier gives us a continuous value anyway that we can threshold.

Could you use a simpler approach without ML? Always be prepared to justify why ML is necessary. For a spam filter, you might say: We could start with regex rules and keyword blocklists, but spammers adapt quickly. ML lets us generalize to new spam patterns without manually updating rules every day.

Step 3: Define the ML Objective

Your ML objective needs to be a quantifiable target that your model can optimize. This is where you bridge business metrics and ML metrics.

Business metric: Increase user engagement on the platform

ML objective: Predict the probability a user will click on or engage with a piece of content

The ML objective should be a proxy for the business metric. The better the proxy, the better your system will perform in practice. But beware of proxy misalignment -- optimizing for clicks might lead to clickbait. Consider using a composite objective that combines multiple signals.

Choosing a Loss Function

Your loss function should align with your ML objective:

| Loss Function | Use Case | How It Works |

|---|---|---|

| Binary cross-entropy | Binary classification | Penalizes confident wrong predictions heavily. Output is probability between 0 and 1. |

| Categorical cross-entropy | Multi-class classification | Extends binary cross-entropy to multiple classes. Used with softmax output. |

| Mean squared error | Regression | Squares the difference between predicted and actual. Penalizes large errors heavily. |

| Mean absolute error | Regression (robust to outliers) | Absolute difference. Less sensitive to outliers than MSE. |

| Pairwise loss (BPR) | Ranking | Optimizes the ordering between pairs of items. Positive items should score higher than negatives. |

| Listwise loss (ListNet) | Ranking | Optimizes the entire ranked list at once. Better theoretical properties but harder to implement. |

| Contrastive loss | Embedding retrieval | Pulls similar items closer and pushes dissimilar items apart in embedding space. |

| Triplet loss | Embedding retrieval | Uses anchor-positive-negative triplets. Requires careful mining of hard negatives. |

| Focal loss | Imbalanced classification | Down-weights easy examples. Focuses training on hard, misclassified examples. |

| Huber loss | Regression (robust) | Combines MSE and MAE. Quadratic for small errors, linear for large errors. |

Multi-Objective Optimization

Many real-world systems optimize for multiple objectives simultaneously. For example, a news feed might want to maximize engagement while maintaining content quality and diversity. Common approaches:

Weighted sum: Combine multiple losses with weights. Simple but requires tuning the weights.

Multi-task learning: Share model parameters across objectives. Each objective has its own head.

Scalarization with constraints: Optimize primary objective subject to constraints on secondary objectives.

Pareto optimization: Find solutions where no objective can be improved without degrading another.

At Meta, the News Feed ranking model optimizes a weighted combination of predicted engagement types -- likes, comments, shares, and meaningful social interactions -- with different weights reflecting the value of each interaction type.

Interview tip: Explicitly state your loss function and explain why it aligns with the business goal. This shows you understand the connection between optimization and product outcomes.

Step 4: Specify Input and Output

Be very explicit about what goes into and comes out of your model.

Input specification:

What features will the model receive? (user features, item features, context features)

What is the feature dimensionality?

Are features dense or sparse?

What is the data type of each feature group?

Output specification:

What does the model predict? (a probability, a score, a class label, an embedding)

What is the output format? (single value, ranked list, probability distribution)

How is the output used downstream? (threshold for decision, sort key for ranking)

Example for a news feed ranking system:

Input: User profile features (age bucket, location, activity level) + article features (topic, author, recency, engagement counts) + context features (time of day, device type, session depth) --> feature vector of approximately 500 dimensions

Output: P(user engages with article) --> float between 0 and 1, used as sort key

Example for a fraud detection system:

Input: Transaction features (amount, merchant category, time since last transaction) + user features (account age, historical transaction patterns, device fingerprint) + contextual features (IP geolocation, time of day) --> feature vector of approximately 200 dimensions

Output: P(transaction is fraudulent) --> float between 0 and 1, thresholded at 0.8 for automatic blocking, 0.5-0.8 for manual review

Example for a search ranking system:

Input: Query features (tokens, intent classification) + document features (title, content, authority score, freshness) + query-document features (BM25 score, semantic similarity) --> feature vector of approximately 300 dimensions

Output: Relevance score --> float used to rank documents, top 10 shown to user

Step 5: Choose the ML Category

Based on your problem framing, identify the learning paradigm:

Supervised learning -- You have labeled data (input-output pairs). This covers most production ML systems: classification, regression, ranking. The workhorse of industry ML. When you have good labels, supervised learning is almost always where you should start.

Unsupervised learning -- No labels. Useful for clustering, dimensionality reduction, anomaly detection. Less common as the primary model but often used for feature engineering or data exploration. For example, at Spotify, unsupervised clustering of listening patterns helps create user segments that become features in the recommendation model.

Self-supervised learning -- Generate labels from the data itself. Increasingly important for pre-training large models (BERT, GPT, contrastive learning for images). Often followed by supervised fine-tuning. At Google, the search ranking model uses self-supervised pre-training on click logs to learn query-document representations before fine-tuning on human relevance labels.

Reinforcement learning -- Learn from sequential interactions and rewards. Used for recommendation systems (contextual bandits), robotics, game playing. More complex to deploy and debug. Contextual bandits are a simpler variant that works well for explore-exploit problems like ad selection or news article recommendation. Full RL is rarely used in production due to complexity, but contextual bandits are common at companies like Netflix (for thumbnail selection) and LinkedIn (for notification optimization).

Semi-supervised learning -- Small amount of labeled data plus large amount of unlabeled data. Useful when labeling is expensive. Techniques include pseudo-labeling (train on labeled data, predict on unlabeled, add confident predictions to training set) and consistency regularization.

In most interviews, you will be in supervised learning territory, sometimes combined with self-supervised pre-training. Know the others well enough to discuss when they are appropriate.

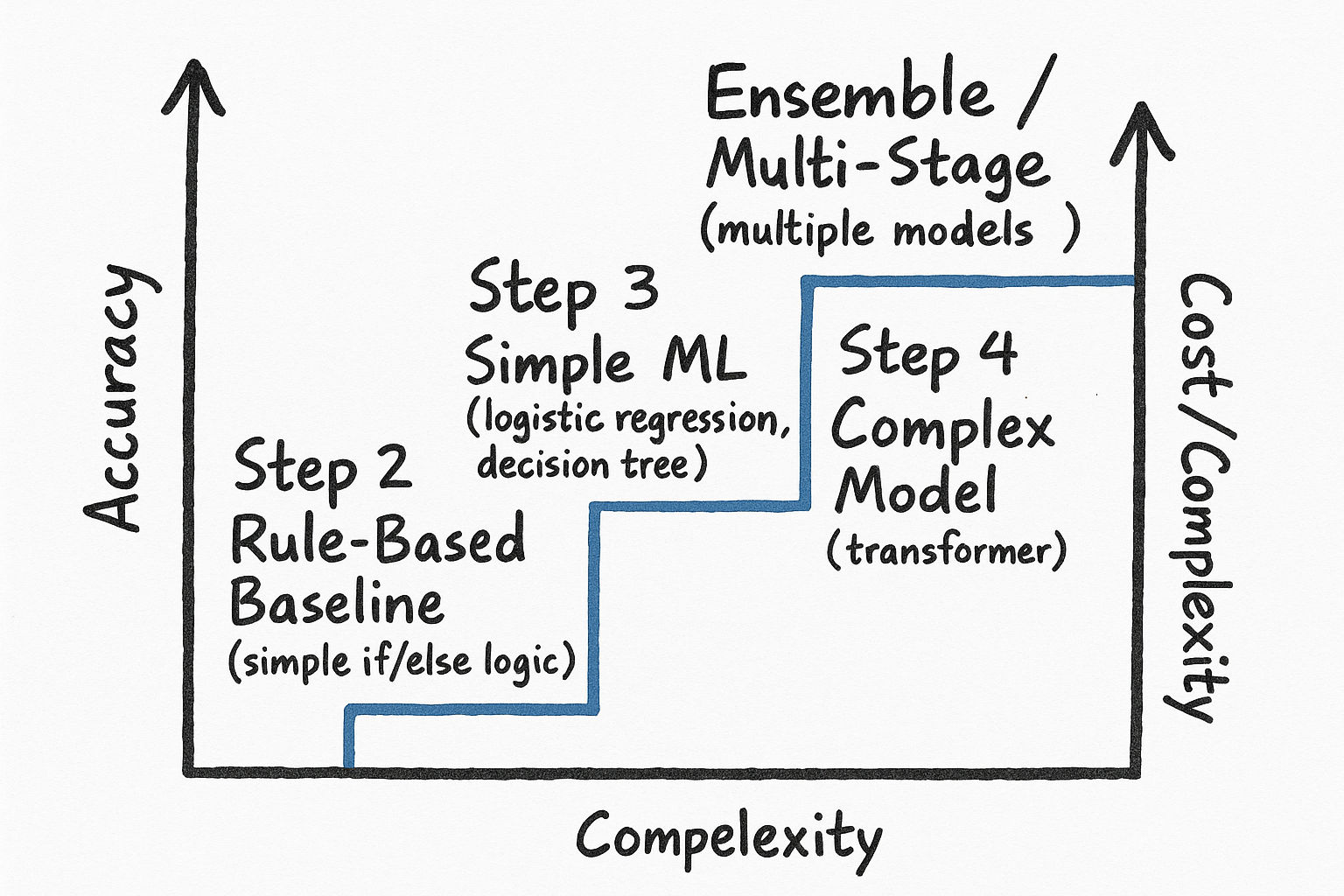

Step 6: Model Development -- Baseline to Complex

This is where you show iterative thinking. Never jump to a complex model first. Walk through a progression:

Stage 1: Baseline (Non-ML)

Start with the simplest possible approach:

Heuristic/rule-based: Sort by popularity, recency, or simple business rules

Random baseline: What is the performance if we predict randomly?

Human performance: What accuracy would a human achieve?

Why? Because you need a baseline to beat. If your ML model cannot beat sort by most recent, something is wrong.

Example for ad click prediction: The simplest baseline is predicting the global average click-through rate for all ads. If the average CTR is 2 percent, predict 0.02 for everything. This gives you a calibrated baseline and tells you the AUC you need to beat (0.5 for random).

Stage 2: Simple ML Model

Pick the simplest ML model that could work:

Logistic regression for classification -- fast to train, fully interpretable, gives you feature importance for free, and forces you to think carefully about features

Linear regression for regression

TF-IDF + logistic regression for text -- surprisingly strong baseline for many NLP tasks

Collaborative filtering for recommendations -- matrix factorization captures user-item interaction patterns

Why start simple? Fast to train, easy to debug, interpretable, good feature importance signals. Often surprisingly competitive. At many companies, the initial production model is a logistic regression that takes weeks to beat with more complex approaches.

Stage 3: Complex Model

Now you can bring in the big guns:

Gradient boosted trees (XGBoost, LightGBM) for tabular data -- the default choice for structured data with mixed feature types. Handles missing values, feature interactions, and non-linear relationships automatically. At Airbnb, the search ranking model used gradient boosted trees for years before transitioning to neural networks.

Deep neural networks for high-dimensional or multi-modal data -- necessary when you have text, images, or very high-dimensional sparse features. At Google, the Wide and Deep model combines a wide linear component (memorization) with a deep neural network (generalization).

Two-tower models for retrieval (user tower + item tower) -- each tower produces an embedding, and similarity between embeddings determines relevance. Used extensively at YouTube, Pinterest, and Meta for candidate retrieval because the item embeddings can be pre-computed and indexed for fast approximate nearest neighbor search.

Transformer-based models for sequential or text data -- BERT for understanding, GPT-style for generation, or custom transformers for behavioral sequences. At Amazon, transformer models process the sequence of user browsing actions to predict purchase intent.

Graph neural networks for social/relational data -- useful when relationships between entities carry signal, such as social networks or knowledge graphs.

Stage 4: Ensemble or Multi-Stage System

For maximum performance:

Ensemble methods: Combine multiple models (averaging, stacking, blending). Different models capture different patterns.

Multi-stage systems: Candidate generation (retrieve 1000 items from millions) --> ranking (score and order the 1000) --> re-ranking (apply business rules, diversity, freshness). This is the standard architecture at Meta, Google, TikTok, and most companies with large-scale recommendation systems.

Specialized models: Different models for different segments. For example, separate models for new users (cold start) vs. established users, or separate models for different content types.

| Stage | Model Type | Latency Budget | Candidates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate generation | Two-tower with ANN index | 10-20ms | Millions to thousands |

| Ranking | Deep neural network or GBDT | 20-50ms | Thousands to hundreds |

| Re-ranking | Rule-based + lightweight model | 5-10ms | Hundreds to tens |

Interview tip: The interviewer wants to see that you can START simple and ADD complexity with justification. Saying I would start with logistic regression as a baseline, then move to gradient boosted trees because we have tabular features with complex interactions is gold.

Step 7: Model Training -- Dataset Construction

Your model is only as good as your training data. This section is where data-savvy candidates shine.

Dataset Construction

What data do you have? User interaction logs, explicit labels, implicit signals

How do you define positive and negative examples? This is critical for classification. For a click prediction model: click = positive, impression without click = negative. But be careful -- not clicking might mean the user did not see the item, not that they were not interested. Consider using dwell time or other engagement signals.

What is your label quality? Are labels noisy? Delayed? Biased?

Labeling Strategies

Natural labels: Derived from user behavior (clicks, purchases, watch time). Cheap and abundant but noisy. A click does not necessarily mean the user liked the content. Watch time is a stronger signal than click.

Human labels: Annotators label data manually. High quality but expensive and slow. At Google, search quality raters evaluate millions of query-result pairs using detailed guidelines. Cost is typically 0.10-1.00 per label depending on complexity.

Programmatic labeling: Use heuristics, knowledge bases, or weak supervision (Snorkel framework) to generate labels at scale. Multiple weak labelers vote and their outputs are combined. Works well when you can define many imperfect rules that together provide strong signal.

Active learning: Selectively label the most informative examples to maximize label efficiency. The model identifies examples near the decision boundary where a human label would be most valuable. Can reduce labeling costs by 50-80 percent compared to random sampling.

Sampling Strategies

Random sampling -- Simple but may miss rare events

Stratified sampling -- Preserve class distribution

Importance sampling -- Over-sample important or rare segments

Negative sampling -- For implicit feedback, sample random items as negatives. Common in recommendation systems. The ratio of negatives to positives matters -- typically 4:1 to 10:1.

Time-based splitting -- Critical for temporal data; train on past, validate on future

Hard negative mining -- Select negatives that are similar to positives. Forces the model to learn fine-grained distinctions. Important for retrieval models.

Train / Validation / Test Split

Random split for i.i.d. data (typical: 80/10/10 or 70/15/15)

Temporal split for time-series or user behavior data (train on weeks 1-8, validate on week 9, test on week 10). This is almost always what you should use in production ML. Random splits for behavioral data lead to data leakage because future information leaks into training.

User-based split for personalization (ensure no user appears in both train and test)

Geographic split if you want to test generalization across regions

Handling Class Imbalance

Most real-world ML problems have imbalanced classes (fraud is rare, spam is less common than ham). Strategies:

| Technique | How It Works | When to Use | Practical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oversampling (SMOTE) | Create synthetic minority examples by interpolating between existing ones | Small datasets, moderate imbalance | Can cause overfitting if done carelessly. Use within cross-validation folds only. |

| Undersampling | Remove majority class examples randomly | Large datasets where you can afford to lose data | Fast and simple. Can lose important majority-class patterns. |

| Class weights | Weight the loss function by inverse class frequency | Simple, works with any model | The go-to first approach. Set weights proportional to 1/class_frequency. |

| Focal loss | Down-weight easy examples, focus on hard ones | Severe imbalance, deep learning | Adds two hyperparameters (alpha and gamma). Gamma=2 is a common starting point. |

| Threshold tuning | Adjust decision threshold post-training | When you need to control precision/recall trade-off | Does not change the model. Use precision-recall curves to find optimal threshold for your use case. |

| Ensemble of resampled models | Train multiple models on different balanced subsets | When you want both diversity and balance | Bagging with balanced bootstraps. More compute but robust. |

Interview tip: Always mention class imbalance if the problem involves rare events (fraud, abuse, disease). It shows you have dealt with real-world data.

Step 8: Training from Scratch vs Fine-Tuning

Training from Scratch

Build a model from randomly initialized weights. Appropriate when:

You have a large, domain-specific dataset (millions of examples)

No pre-trained model exists for your domain

Your task is fundamentally different from what pre-trained models were trained on

Your data distribution is very different from pre-training data

Fine-Tuning (Transfer Learning)

Start from a pre-trained model and adapt it to your task. Appropriate when:

You have limited labeled data (hundreds to low thousands of examples)

A pre-trained model exists in a related domain (ImageNet for vision, BERT for text)

You want faster training and better performance

Your task is related to what the pre-trained model learned

Common fine-tuning strategies:

| Strategy | Description | When to Use | Typical Learning Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature extraction | Freeze pre-trained layers, train only final head | Very small dataset (under 1K examples), or quick experiment | 1e-3 to 1e-2 for new head |

| Full fine-tuning | Unfreeze all layers, train end-to-end | Medium dataset (1K-100K examples), task similar to pre-training | 1e-5 to 1e-4 (small LR crucial) |

| Progressive unfreezing | Gradually unfreeze layers from top to bottom | Medium dataset, want more control over adaptation | Start 1e-3, reduce as you unfreeze deeper layers |

| LoRA / Adapters | Add small trainable modules, keep base frozen | Large pre-trained model, limited compute | 1e-4 for adapter parameters |

In 2025, fine-tuning pre-trained foundation models is the default starting point for text, image, and multi-modal tasks. Mention this in interviews -- it shows you are current. For tabular data, however, training from scratch with gradient boosted trees is still the dominant approach.

Step 9: Distributed Training

For large models or large datasets, training on a single machine is not feasible. Know the two main approaches:

Data parallelism: Split the data across multiple GPUs/machines. Each worker has a full copy of the model and processes a different mini-batch. Gradients are synchronized (all-reduce) after each step.

Simple to implement (PyTorch DistributedDataParallel handles most of it)

Works well when the model fits in a single GPU memory

Communication overhead scales with model size

Near-linear speedup for 2-8 GPUs, diminishing returns beyond that due to communication costs

Synchronous: All workers wait for gradients from all others. Slower but more stable training.

Asynchronous: Workers update independently. Faster but can lead to stale gradients and training instability.

Model parallelism: Split the model across multiple GPUs. Different layers or components live on different devices.

Pipeline parallelism: Different layers on different GPUs. Forward pass flows through GPUs sequentially. Micro-batching helps with GPU utilization.

Tensor parallelism: Single layers are split across GPUs. Each GPU computes part of a matrix multiplication. Used for very large transformer layers.

Necessary when the model does not fit on one GPU (common for large language models)

More complex to implement

Practical guidance for interviews: For most problems, briefly mentioning we would use data parallelism across N GPUs with synchronized gradient updates is sufficient. Only go deep if the interviewer asks or the problem involves very large models. If training a model with billions of parameters, mention combining data parallelism with pipeline parallelism (this is what Meta and Google do for their largest models).

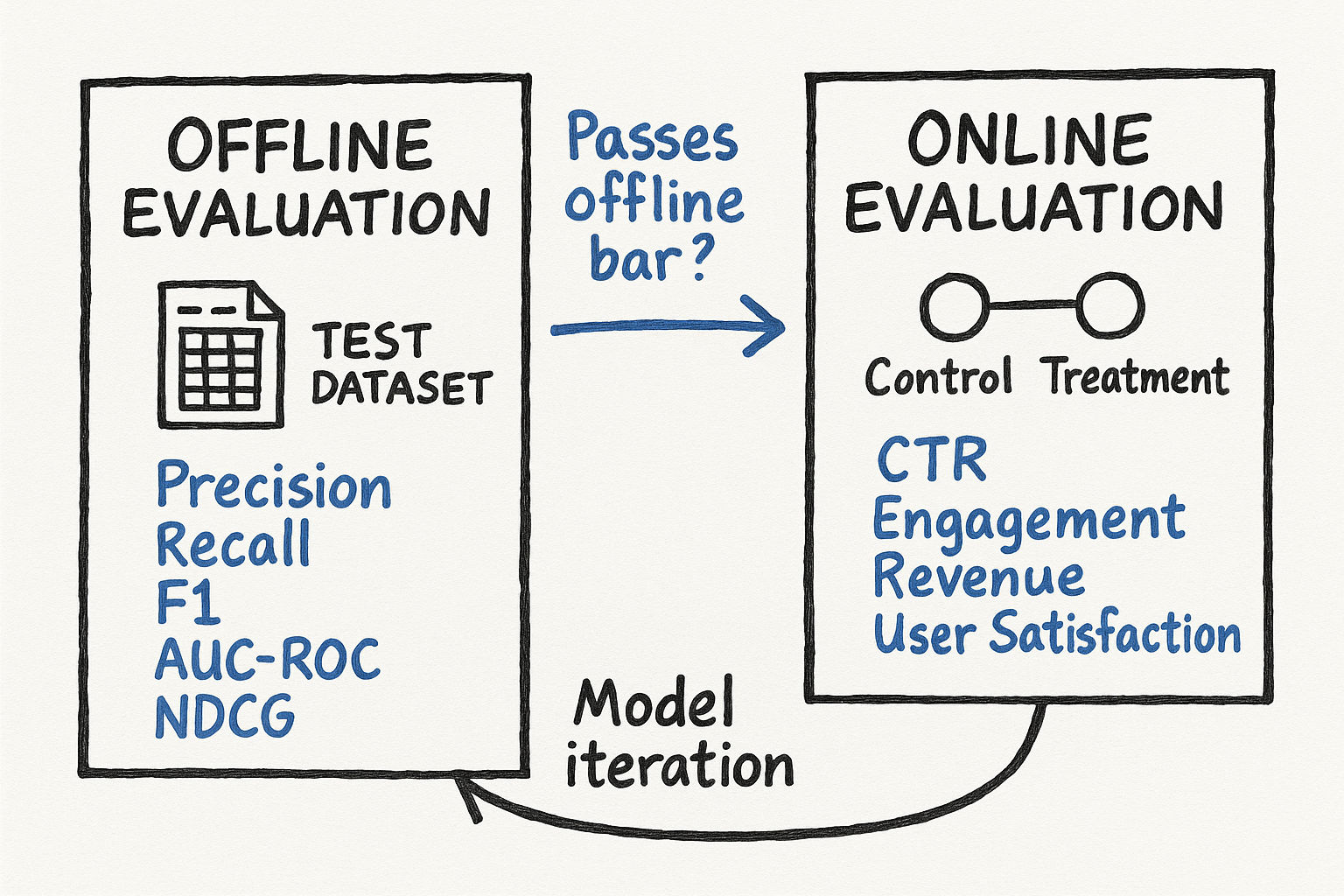

Step 10: Evaluation -- Offline and Online Metrics

Evaluation is where you connect your ML work back to business impact. You need BOTH offline and online metrics.

Offline Metrics (Measured Before Deployment)

Classification metrics with intuitive explanations:

Precision: Of all items we predicted positive, how many were actually positive? Formula: TP / (TP + FP). High precision means few false alarms. Important when the cost of a false positive is high (wrongly blocking a legitimate transaction).

Recall: Of all actual positives, how many did we catch? Formula: TP / (TP + FN). High recall means we miss very few positives. Important when the cost of a false negative is high (missing fraudulent transactions).

F1 Score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall. Formula: 2 (Precision Recall) / (Precision + Recall). Use when you want a single number that balances both. The harmonic mean penalizes extreme imbalances -- if either precision or recall is low, F1 will be low.

AUC-ROC: Model ability to distinguish between classes across all thresholds. Plots true positive rate vs. false positive rate. AUC of 0.5 = random, 1.0 = perfect. Useful because it is threshold-independent. A model with AUC 0.85 means that a randomly chosen positive example will be ranked higher than a randomly chosen negative example 85 percent of the time.

AUC-PR (Precision-Recall AUC): More informative than AUC-ROC for imbalanced datasets. When 99.9 percent of transactions are legitimate, AUC-ROC can look high even for a weak model. AUC-PR focuses on the minority class performance.

Log loss: Measures calibration -- how well predicted probabilities match actual frequencies. A model predicting 0.3 probability for events that happen 30 percent of the time has good calibration. Important for ad click prediction where bid prices are based on predicted probabilities.

Ranking metrics with intuitive explanations:

NDCG (Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain): Measures ranking quality with position-weighted relevance. Items higher in the ranking contribute more to the score. The discounting factor (log2 of position) means the top result matters much more than the 10th result. NDCG at 10 is the most common variant.

MAP (Mean Average Precision): Average of precision values calculated at each relevant item in the ranked list. Rewards putting all relevant items high in the list. Works best with binary relevance (relevant vs. not relevant).

MRR (Mean Reciprocal Rank): The reciprocal of the rank of the first relevant result, averaged across queries. If the first relevant result is at position 3, MRR for that query is 1/3. Good for navigational queries where the user wants one specific answer.

Precision at K / Recall at K: Precision and recall computed only in the top K results. Precision at 10 means: of the top 10 results, how many are relevant? Practical because users rarely look beyond the first page.

Regression metrics:

MSE / RMSE: Penalizes large errors heavily due to squaring. RMSE is in the same units as the target, making it interpretable. If RMSE for delivery time prediction is 5 minutes, typical errors are around 5 minutes.

MAE: Average absolute error, more robust to outliers. If a few deliveries are extremely late, MAE is less affected than RMSE.

MAPE: Mean absolute percentage error. Useful when errors should be relative -- a 5-minute error on a 10-minute delivery is worse than a 5-minute error on a 60-minute delivery.

R-squared: Proportion of variance explained. R-squared of 0.9 means the model explains 90 percent of the variation in the target.

Online Metrics (Measured After Deployment)

Online metrics are the real measure of success. They capture what actually happens when real users interact with your system:

CTR (Click-Through Rate): Fraction of impressions that result in clicks

Conversion rate: Fraction of users who complete a desired action

Revenue per user: Direct business impact

Engagement metrics: Time spent, sessions per day, content consumed

User satisfaction: NPS scores, ratings, survey responses, long-term retention

Guardrail metrics: Things that should NOT degrade (page load time, content diversity, fairness metrics across demographics)

A/B Testing Best Practices

Randomization unit: Usually user-level (not session or request level) to avoid inconsistent experiences

Sample size: Use power analysis to determine required sample size before launching. Typically need thousands of users per variant for reliable results.

Duration: Run for at least 1-2 weeks to capture weekly patterns. Avoid ending tests on weekends if weekday behavior differs.

Multiple testing correction: If testing multiple metrics, apply Bonferroni correction or use a primary metric with secondary guardrails.

Novelty effects: New features sometimes show initial lift that fades. Consider running for longer (3-4 weeks) for major changes.

Interview tip: Always connect offline metrics to online metrics. Say something like: We will optimize for AUC-ROC offline, but the true success metric is a lift in DAU engagement measured through an A/B test.

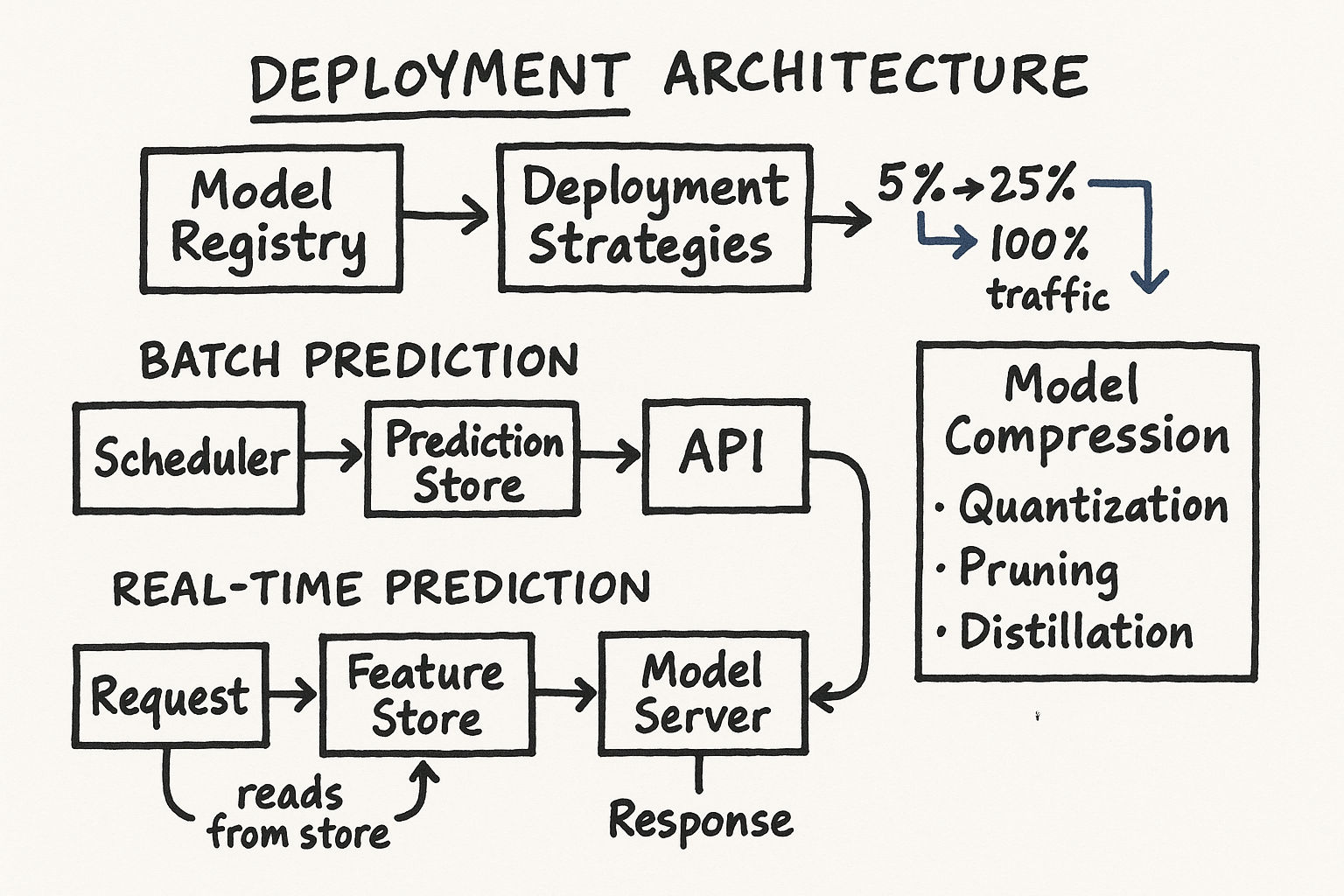

Step 11: Deployment and Serving

Your model needs to make predictions in production. This is where ML engineering meets software engineering.

Cloud vs On-Device

Cloud serving: Model runs on servers. Allows larger models, easier updates, but requires network round-trip. Latency depends on network (typically 10-50ms overhead). Best for complex models where accuracy matters more than latency.

On-device (edge): Model runs on user phone or device. Lower latency (under 10ms), works offline, preserves privacy (data stays on device), but model size is constrained (typically under 50MB). Best for real-time applications like keyboard prediction, face detection, or voice commands.

Model Compression Techniques

Quantization reduces numerical precision:

| Type | From | To | Speedup | Accuracy Loss | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP16 (half precision) | FP32 | FP16 | 1.5-2x | Negligible | Default for GPU inference |

| INT8 (post-training) | FP32 | INT8 | 2-4x | Small (0.1-0.5%) | CPU inference, edge devices |

| INT8 (quantization-aware training) | FP32 | INT8 | 2-4x | Minimal | When post-training quantization loses too much |

| INT4 / Binary | FP32 | INT4/1-bit | 4-8x | Moderate | Extreme edge constraints |

Pruning removes unimportant weights:

Unstructured pruning: Zero out individual weights below a threshold. Can achieve 90 percent sparsity but requires sparse matrix support for actual speedup.

Structured pruning: Remove entire neurons, channels, or attention heads. Directly reduces model size and computation without special hardware support.

Iterative magnitude pruning: Train, prune smallest weights, retrain, repeat. The lottery ticket hypothesis suggests there exists a small subnetwork that trains as well as the full model.

Knowledge distillation: Train a smaller student model to mimic a larger teacher model. The teacher provides soft labels (probability distributions over classes) that contain more information than hard labels. Temperature scaling controls how soft the distributions are. At Google, DistilBERT achieves 97 percent of BERT performance with 40 percent fewer parameters.

Deployment Strategies

| Strategy | Risk Level | Rollout Speed | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shadow deployment | Very low | Slow | Initial validation, no user impact |

| Canary deployment | Low | Medium | Testing with small real traffic |

| A/B testing | Medium | Slow (need statistical significance) | Measuring business impact |

| Blue-green deployment | Medium | Fast (instant switch) | Quick rollbacks needed |

| Feature flags | Low | Variable | Gradual rollout with kill switch |

Prediction Pipeline: Batch vs Real-Time

| Approach | Latency | Freshness | Cost | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch prediction | N/A (pre-computed) | Stale (hours/days) | Low (run overnight) | Email recommendations, daily reports |

| Real-time (online) prediction | Low (ms) | Fresh | High (always-on infra) | Search ranking, fraud detection |

| Near-real-time | Medium (seconds) | Semi-fresh | Medium | Feed ranking with recent signals |

| Hybrid | Mixed | Mixed | Medium-High | Pre-compute candidates in batch, re-rank in real-time |

Many production systems combine batch and real-time: pre-compute candidate items in batch, then re-rank in real-time using fresh features. This is the standard pattern at companies like Netflix (pre-compute candidate shows per user nightly, re-rank based on current session context at request time).

Step 12: Monitoring and Maintenance

Deploying a model is not the end -- it is the beginning. ML systems degrade over time, and monitoring is how you catch problems before users do.

Why ML Systems Fail

Data drift: The distribution of input data changes over time. Example: user behavior shifts during holidays, a pandemic changes search patterns, a new product category is added. Detect using statistical tests (KS test, PSI) on feature distributions.

Concept drift: The relationship between inputs and outputs changes. Example: what users consider relevant content evolves, fraud patterns change as attackers adapt, economic conditions shift price sensitivity. Harder to detect than data drift because you need ground truth labels which may be delayed.

Feedback loops: The model predictions influence future training data. Example: a recommendation system that only shows popular items will only get engagement data on popular items, reinforcing its bias toward popular content and starving niche content of exposure. This is called popularity bias and is one of the most common failure modes in recommendation systems.

Silent failures: Unlike traditional software that crashes with an error, ML models fail silently -- they keep making predictions, just bad ones. Your monitoring system needs to catch these degradations.

What to Monitor -- Building Your Dashboard

Data quality dashboard:

Feature distribution shifts (PSI score for each key feature, alert if PSI > 0.2)

Missing value rates by feature (alert if any feature exceeds historical baseline by 2x)

Data pipeline freshness and latency (alert if features are more than X hours stale)

Schema violations (new categories, unexpected data types)

Input volume (alert on sudden drops or spikes indicating pipeline issues)

Model performance dashboard:

Daily offline metric trends (AUC, precision, recall computed on recent labeled data)

Prediction distribution shifts (mean and variance of prediction scores over time)

Calibration plots (are predicted probabilities still accurate?)

Performance across segments (by region, device, user cohort, content type)

Comparison between model versions if running A/B tests

System health dashboard:

Prediction latency (p50, p95, p99) with SLA thresholds

Throughput (predictions per second)

Error rates (model serving errors, feature fetch failures, timeouts)

Resource utilization (CPU, GPU, memory)

Cache hit rates for feature stores and model caches

When to Retrain

| Strategy | Frequency | Trigger | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scheduled retraining | Daily, weekly, monthly | Calendar | Stable domains with regular data updates |

| Triggered retraining | As needed | Performance drop below threshold | When drift is unpredictable |

| Continuous training | Continuous | New data arrival | Fast-moving domains (ads, recommendations) |

| Champion-challenger | Ongoing | New model beats current | When you want automated model selection |

At companies like Google and Meta, ad ranking models retrain continuously -- sometimes multiple times per day -- because user behavior and advertiser campaigns change rapidly. Content recommendation models at Netflix retrain daily. Fraud detection models at Stripe retrain weekly but have real-time rule updates for emerging fraud patterns.

Interview tip: Mentioning monitoring unprompted is a strong signal. Say something like: Once deployed, I would monitor for data drift using PSI on key features, track daily AUC trends, and set up alerts if prediction latency exceeds our p99 SLA.

Putting It All Together: The Quick Reference

Here is your 12-step framework on one page. Use this as your mental checklist in every interview:

| Step | Key Question | Time Allocation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Clarify requirements | What are we building and for whom? | 5-8 min |

| 2. Frame as ML problem | Is ML the right approach? What type? | 2-3 min |

| 3. Define ML objective | What metric does the model optimize? | 2-3 min |

| 4. Specify input/output | What goes in, what comes out? | 2-3 min |

| 5. Choose ML category | Supervised? Self-supervised? | 1-2 min |

| 6. Model development | Baseline to simple to complex | 5-8 min |

| 7. Training data | Labels, sampling, imbalance | 5-7 min |

| 8. Training approach | Scratch vs fine-tuning | 2-3 min |

| 9. Distributed training | Data/model parallelism | 1-2 min |

| 10. Evaluation | Offline + online metrics | 3-5 min |

| 11. Deployment | Serving, compression, A/B testing | 3-5 min |

| 12. Monitoring | Drift, alerts, retraining | 3-5 min |

You do not need to spend equal time on every step. Adapt based on the problem and where the interviewer wants to go deep. But touch every step at least briefly -- completeness matters.

Key Takeaways

This 12-step framework works for ANY ML system design problem

Start every interview with requirement clarification -- it shapes everything downstream

Always show iterative model development: baseline to simple to complex

Connect offline metrics to online business metrics

Do not forget deployment, serving, and monitoring -- they separate senior from junior candidates

Know your loss functions and why each one aligns with specific problem types

Understand the trade-offs in model compression: quantization types, pruning strategies, and distillation

Build mental models for A/B testing, monitoring dashboards, and retraining strategies

Practice applying this framework to 10-15 different problems and it will become second nature