1.3 Data Preparation and Feature Engineering

Data Preparation and Feature Engineering

Here is an uncomfortable truth about production ML: the model you choose matters far less than the data you feed it. I have seen simple logistic regression models with excellent features outperform deep neural networks with poorly engineered inputs. Time and time again.

In ML system design interviews, your ability to discuss data preparation and feature engineering signals whether you have actually built ML systems or just read about them. This lesson covers everything you need to know.

Data Engineering Fundamentals

Before you can engineer features, you need data. And before you can use data, you need to understand where it comes from and how it is stored.

Data Sources

In a typical ML system at a tech company, data comes from multiple sources:

User interaction logs -- Clicks, views, scrolls, purchases, search queries, session duration. This is usually your richest data source. Stored in event logging systems (Kafka, Kinesis) and eventually lands in a data warehouse. At Meta, every interaction on the platform generates an event that flows through their logging pipeline -- billions of events per day. These logs contain the implicit feedback signals that power most recommendation and ranking models.

Application databases -- User profiles, product catalogs, content metadata. Structured data in relational databases (PostgreSQL, MySQL) or NoSQL stores (DynamoDB, MongoDB). This data changes less frequently but provides important entity attributes.

Third-party data -- Demographics, geolocation, market data, external APIs. Can enrich your features but introduces dependencies and privacy concerns. For example, weather data can be a powerful feature for food delivery ETA prediction (Uber Eats uses this), and economic indicators can help demand forecasting models.

User-generated content -- Reviews, comments, posts, images, videos. Unstructured data that requires NLP or computer vision to extract features. At Amazon, product review text is processed through NLP models to extract sentiment scores, key product attributes, and quality signals that become features in the search ranking model.

Derived / aggregated data -- Pre-computed statistics like average user session length over the past 30 days or number of purchases in the last week. Often stored in feature stores. These aggregated features are some of the most powerful inputs to ML models because they compress historical behavior into informative signals.

Data Storage: Warehouse vs Lake

| Aspect | Data Warehouse | Data Lake |

|---|---|---|

| Data format | Structured, schema-on-write | Raw, schema-on-read |

| Query engine | SQL (BigQuery, Redshift, Snowflake) | Spark, Presto, Hive |

| Use case | Analytics, reporting, ML training | Raw data storage, exploration |

| Cost | Higher (optimized for queries) | Lower (cheap blob storage like S3) |

| Data quality | Clean, validated | Raw, potentially messy |

| Schema evolution | Strict, migrations required | Flexible, new fields easy to add |

Most ML teams use both: raw data lands in the data lake, gets cleaned and transformed via ETL pipelines, and the processed version is loaded into the data warehouse for model training. At Netflix, raw event logs land in S3 (data lake), get processed through Spark jobs, and the cleaned features are loaded into Snowflake (data warehouse) for training data construction.

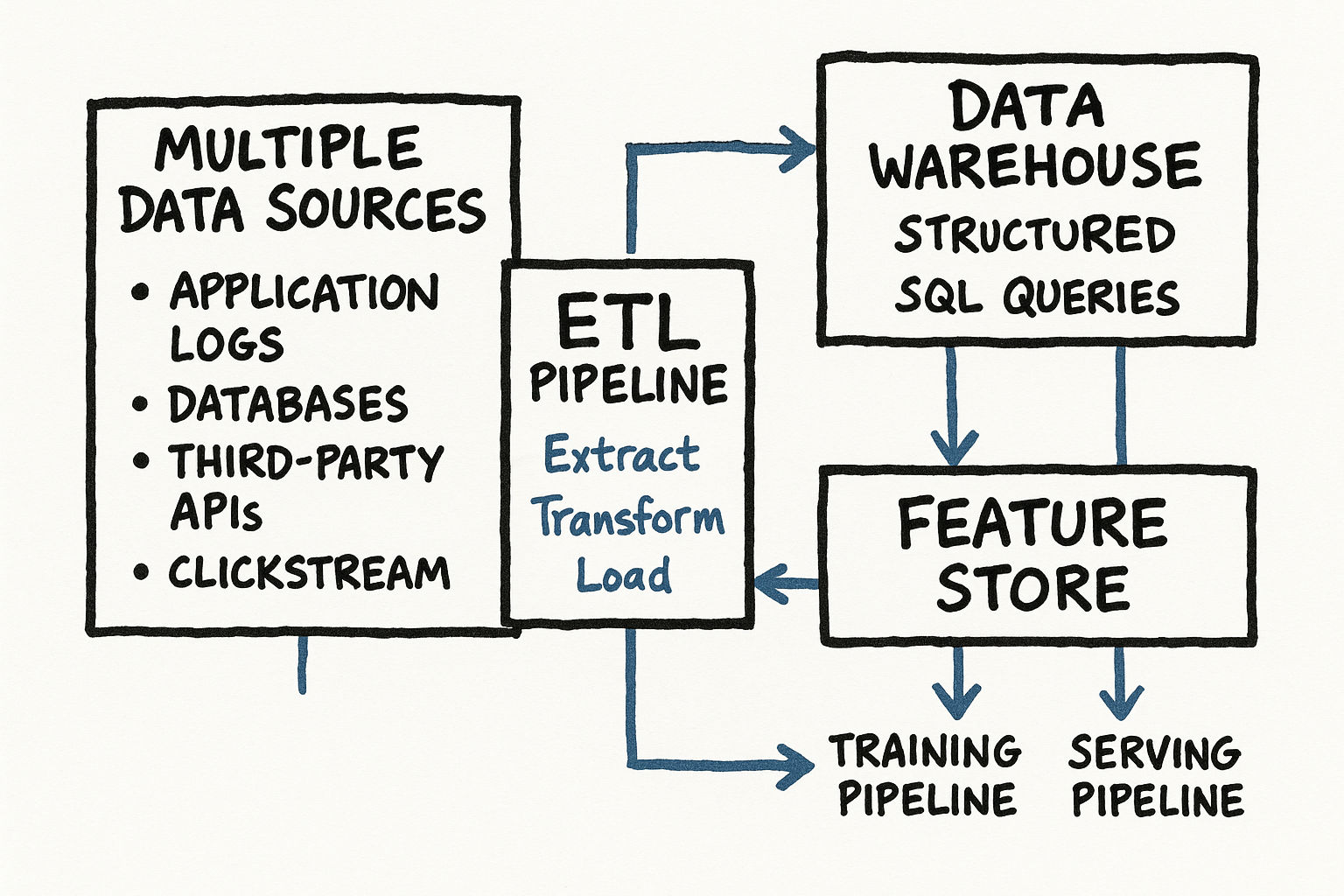

ETL Pipelines

Extract, Transform, Load -- the backbone of data engineering:

Extract: Pull data from source systems (databases, APIs, event streams)

Transform: Clean, validate, aggregate, join, and compute features

Load: Write processed data to destination (warehouse, feature store, training dataset)

Tools you might mention in interviews: Apache Airflow (workflow orchestration), dbt (SQL-based transformations), Apache Spark (distributed processing), Google Dataflow (streaming and batch), Prefect (modern workflow orchestration).

Interview tip: You do not need to design the entire data pipeline in detail, but showing awareness that data does not magically appear in a clean CSV demonstrates real-world experience.

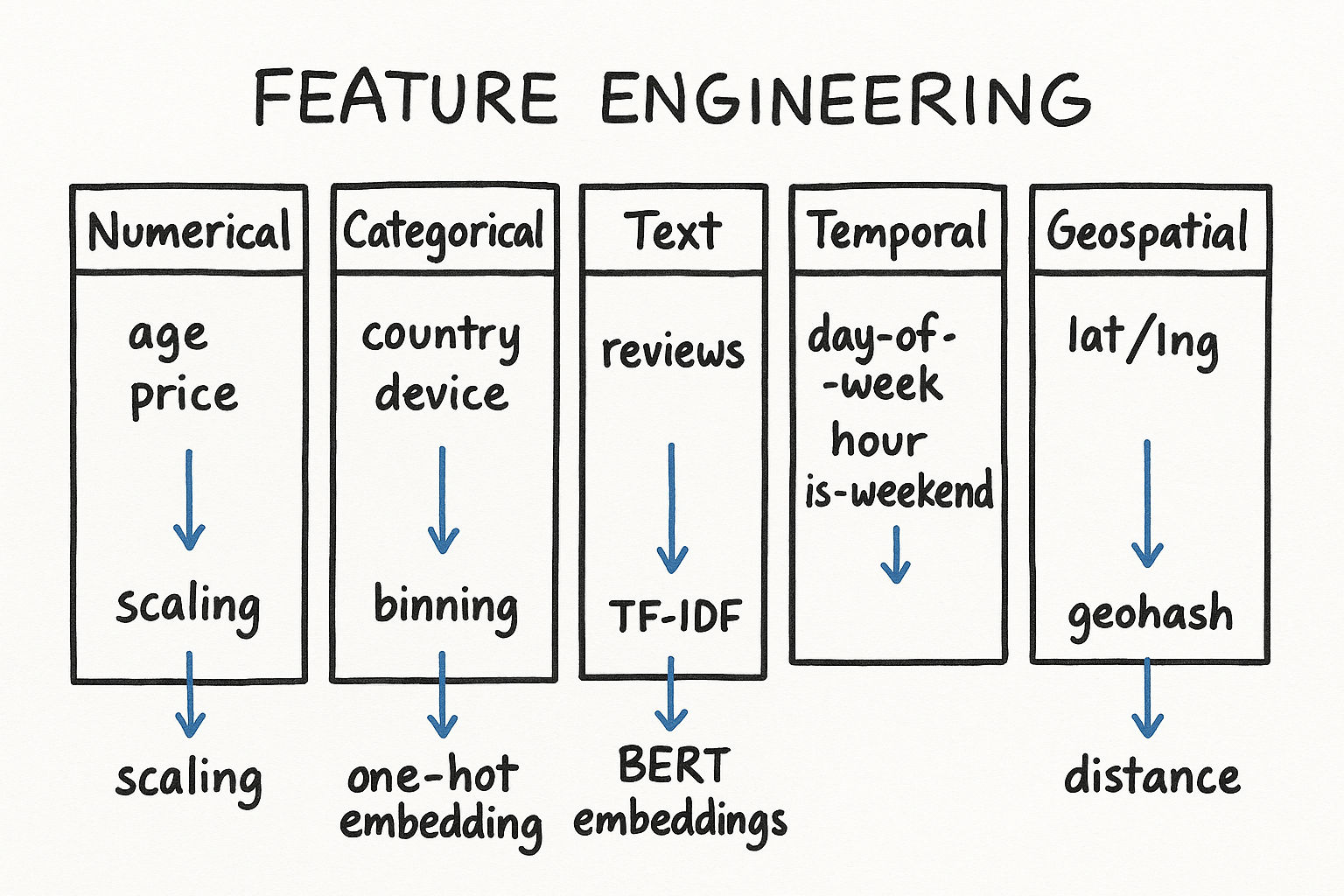

Data Types

Understanding data types determines which feature engineering techniques you can apply.

Numerical Features

Continuous: Temperature, price, age, latency. Can take any value in a range.

Discrete: Number of clicks, number of friends, count of purchases. Integer values.

Categorical Features

Nominal: No inherent order. Examples: country, color, product category, user ID.

Ordinal: Has a meaningful order. Examples: education level (high school, bachelors, masters, PhD), satisfaction rating (1-5).

Text Features

Raw text that needs to be converted to numerical representations through tokenization, embedding, or bag-of-words approaches. Examples: product descriptions, user reviews, search queries.

Temporal Features

Timestamps, dates, durations. Often transformed into cyclical features (hour of day, day of week) or relative features (time since last action, recency).

Geospatial Features

Latitude/longitude, regions, distances. Used heavily in ride-sharing (Uber, Lyft) and local search applications.

Knowing the type matters because it determines your encoding strategy. You would not one-hot encode a continuous variable, and you would not apply z-score normalization to a categorical one.

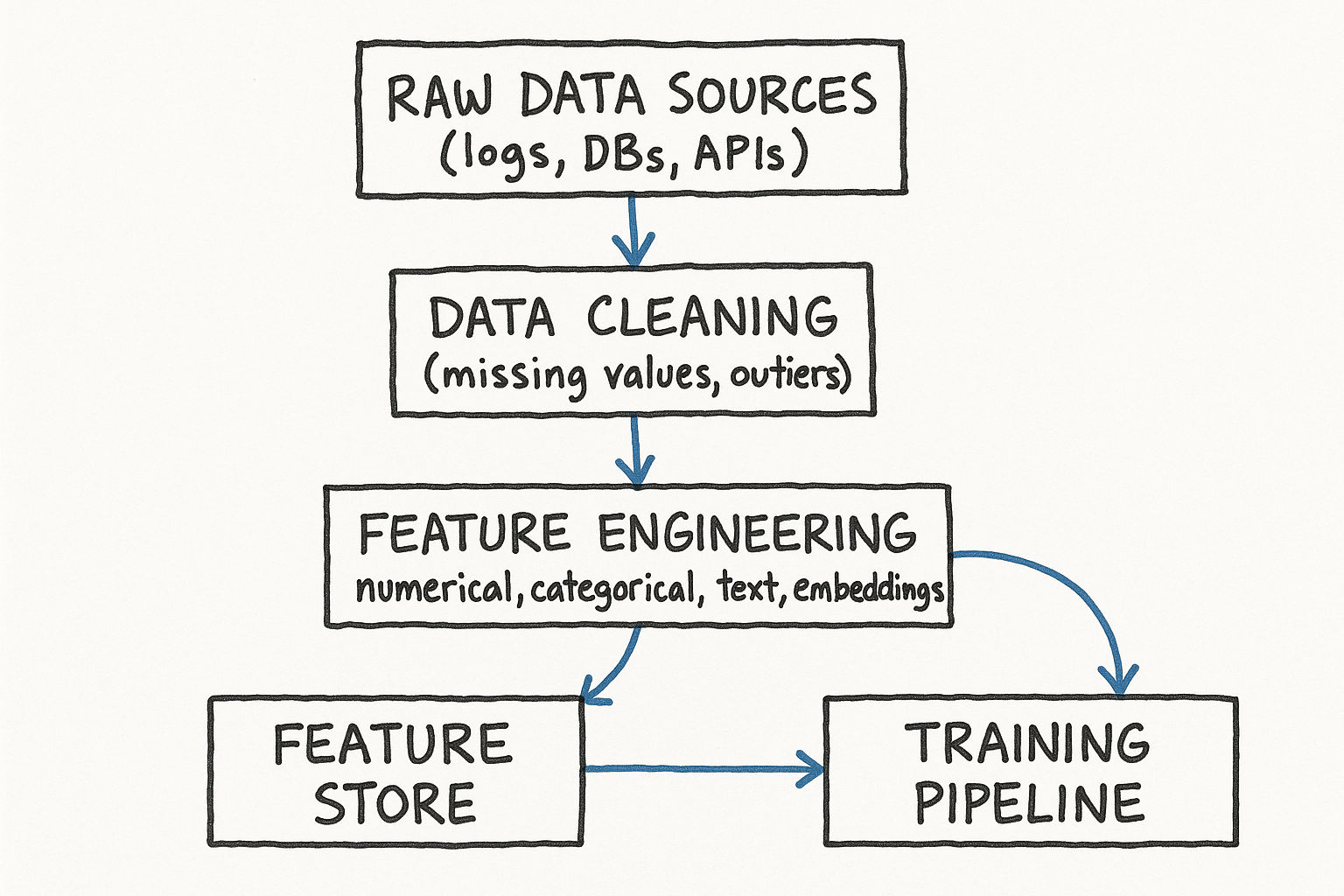

Feature Engineering: Why It Matters More Than Model Choice

Feature engineering is the process of transforming raw data into inputs that help ML models learn patterns more effectively.

Consider two approaches to building a click prediction model:

Approach A: Feed raw user ID and item ID into a deep neural network. Let the model figure everything out.

Approach B: Engineer features like user click rate in the past 7 days, item popularity score, time since user last session, and similarity between this item and items the user previously engaged with.

Approach B will almost always win, especially with limited data. Good features encode domain knowledge that would take the model enormous amounts of data to discover on its own.

Types of Features in ML Systems

User features: Demographics, behavior aggregates, preferences, account age, activity level, subscription tier

Item features: Category, popularity, recency, content attributes, price, creator quality score

Context features: Time of day, day of week, device type, location, session length, network type

Interaction features: User-item cross features, historical engagement between this user and similar items, co-engagement patterns

Graph features: Social connections, co-purchase patterns, influence scores, degree centrality

Real-World Feature Engineering Examples

Ad click prediction (Meta, Google):

User historical CTR on similar ads (past 7 days, 30 days)

Ad creative quality score (image resolution, text length, emoji usage)

Advertiser reputation score

Time since user last clicked an ad (ad fatigue signal)

User-ad category affinity (how much does this user engage with ads in this category)

Position bias features (ads at the top of the page get more clicks regardless of relevance)

Recommendation system (Netflix, Spotify):

User genre preferences (weighted average of genres consumed)

Item freshness (days since release)

Collaborative filtering similarity scores (how similar is this item to items the user liked)

Popularity trajectory (is this item trending up or down)

Time-of-day preferences (users watch different content at different times)

Completion rate (fraction of similar content the user finished)

Fraud detection (Stripe, PayPal):

Transaction velocity (number of transactions in the last hour)

Amount deviation from user average

Geographic distance from usual location

Device fingerprint match

Time since account creation

Merchant risk score

Card-not-present indicator

Shipping address vs. billing address mismatch

Search ranking (Google, Amazon):

BM25 text relevance score

Query-document semantic similarity (embedding cosine similarity)

Document authority score (PageRank, review count)

Click-through rate for this query-document pair historically

Document freshness

User location relevance

Query intent classification (navigational, informational, transactional)

Handling Missing Values

Real-world data is messy. Missing values are everywhere, and how you handle them matters.

Deletion Approaches

Listwise deletion: Remove any row with a missing value. Simple but you lose data. Only viable if missingness is rare (under 5 percent) and random (MCAR -- Missing Completely At Random). In practice, data is rarely MCAR -- users who skip fields tend to be systematically different from those who fill them in.

Pairwise deletion: Use all available data for each calculation. Different analyses may use different subsets of rows. Can lead to inconsistencies but preserves more data.

Imputation Approaches

| Method | How It Works | Pros | Cons | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/Median | Replace missing with column mean or median | Simple, fast, preserves mean | Does not capture relationships, reduces variance | Quick baseline, numerical features with low missingness |

| Mode | Replace with most frequent value (categorical) | Simple | Does not capture relationships | Categorical features with dominant category |

| KNN imputation | Use K nearest neighbors to estimate missing value | Captures local patterns, respects feature relationships | Slow for large datasets (O(n^2)), sensitive to K choice | Small-medium datasets where relationships matter |

| Regression imputation | Predict missing value using other features as predictors | Captures linear relationships | Can overfit, underestimates variance | When strong linear relationships exist between features |

| MICE | Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations -- iteratively impute each feature using others | Handles complex patterns, provides uncertainty estimates | Computationally expensive, requires multiple imputed datasets | Research settings, when imputation uncertainty matters |

| Missing indicator | Create binary flag (is_missing=1) plus impute with constant (0 or median) | Preserves missingness signal, simple to implement | Increases dimensionality | Best default approach for tree-based models |

| Model-specific handling | XGBoost and LightGBM handle missing values natively | No preprocessing needed, learns optimal split direction | Only works with specific models | When using gradient boosted trees |

Practical advice for interviews: For numerical features, median imputation plus a missing indicator flag is a solid default. Median is robust to outliers (unlike mean). For categorical features, treat missing as its own category -- this often works better than imputing with the mode because missingness itself can be informative. For example, a missing income field might indicate the user chose not to share it, which is a signal about their privacy preferences.

Interview tip: Simply saying you would handle missing values is not enough. Specify your strategy and explain why. For features with less than 5 percent missing, impute with the median and add a binary missing indicator. For features with more than 30 percent missing, evaluate whether to drop the feature entirely or whether the missingness pattern itself is informative.

Feature Scaling

Most ML models are sensitive to feature scale. A feature ranging from 0-1 and another from 0-1000000 will cause problems for gradient-based models.

Normalization (Min-Max Scaling)

Rescales features to a fixed range, typically [0, 1]:

x_normalized = (x - x_min) / (x_max - x_min)

When to use: When you need bounded values. Works well for neural networks and distance-based algorithms (KNN, K-means). Sensitive to outliers -- a single extreme value can compress all other values into a tiny range.

Standardization (Z-Score Scaling)

Centers features to mean=0, std=1:

x_standardized = (x - mean) / std

When to use: Default choice for most models. Works well for linear models, SVMs, and neural networks. Less sensitive to outliers than min-max. Important: compute mean and std on the training set only, then apply the same transformation to validation and test sets.

Robust Scaling

Uses median and interquartile range instead of mean and std:

x_robust = (x - median) / IQR

When to use: When your data has significant outliers. The median and IQR are not affected by extreme values, making this more robust than standardization.

Log Scaling

Apply logarithmic transformation: x_log = log(1 + x)

When to use: For highly skewed features (income, page views, follower count). Compresses the range and makes the distribution more normal-like. The +1 handles zero values. At Instagram, follower counts are log-transformed before being used as features because the distribution is extremely right-skewed (most users have few followers, a few have millions).

Power Transforms (Box-Cox, Yeo-Johnson)

Automatically find the best transformation to make the distribution more Gaussian-like. Box-Cox requires positive values; Yeo-Johnson handles zeros and negatives.

When Scaling Does Not Matter

Tree-based models (decision trees, random forests, XGBoost) are invariant to feature scaling because they make splits based on feature values, not distances. This is one reason tree-based models are so popular for tabular data -- less preprocessing needed. However, if you are using tree-based models combined with linear components (like in a Wide and Deep model), you still need to scale the features going into the linear part.

Discretization and Binning

Sometimes converting continuous features into discrete bins improves model performance or interpretability.

Equal-Width Binning

Divide the range into N bins of equal width. Example: age into [0-18, 18-30, 30-45, 45-60, 60+].

Equal-Frequency Binning (Quantile Binning)

Each bin contains approximately the same number of examples. Better for skewed distributions. Example: if income is highly skewed, equal-width bins would put 90 percent of examples in the first bin. Quantile binning ensures each bin has 20 percent of the data.

Why Bin?

Captures non-linear relationships in linear models

Reduces sensitivity to outliers

Can improve model robustness

Makes features more interpretable

Enables feature crosses with categorical variables

Example: Raw income might be noisy, but income bracket (low/medium/high) captures the signal that matters for predicting purchasing behavior. At Google, continuous features in the ad ranking model are bucketized into quantile bins before being used in the wide component of the Wide and Deep model.

Encoding Categorical Features

ML models need numbers, not strings. How you encode categorical features significantly impacts model performance.

One-Hot Encoding

Create a binary column for each category. color = red becomes [1, 0, 0] for [red, blue, green].

Pros: Simple, no ordinal assumption, works with any model

Cons: High dimensionality for high-cardinality features (imagine one-hot encoding user_id with 100M users)

Use when: Low to moderate cardinality (under 100 categories)

Label Encoding

Assign each category an integer. red=0, blue=1, green=2.

Pros: Low dimensionality, memory efficient

Cons: Implies ordinal relationship that may not exist

Use when: Tree-based models (they handle this well because they split on individual values), ordinal features

Target Encoding (Mean Encoding)

Replace each category with the mean of the target variable for that category. For city encoding in a house price model: each city gets replaced with the average house price in that city.

Pros: Captures relationship with target, works for high cardinality, low dimensionality

Cons: Risk of target leakage -- must use proper cross-validation or smoothing

Use when: High-cardinality features with strong target correlation

Implementation detail: Use leave-one-out encoding or fold-based encoding to prevent leakage. Add smoothing: encoded_value = (count category_mean + global_count global_mean) / (count + global_count) where global_count is a smoothing parameter.

Embedding-Based Encoding

Learn a dense vector representation for each category. This is what neural networks do with embedding layers.

Pros: Captures semantic similarity (similar categories get similar embeddings), low dimensionality, powerful representation

Cons: Requires neural network training, needs sufficient data per category

Use when: Very high cardinality (user IDs, product IDs), deep learning models

Implementation: Typical embedding dimension is between 8 and 128, often following the rule of thumb: min(50, cardinality / 2). At Airbnb, listing embeddings are trained using Word2Vec-style approaches on user click sequences -- listings that users click sequentially end up with similar embeddings.

Feature Hashing (Hashing Trick)

Hash category values into a fixed-size vector. No need to maintain a vocabulary.

Pros: Fixed memory, handles unseen categories gracefully, fast, no need for dictionary maintenance

Cons: Hash collisions lose information, not invertible

Use when: Very high cardinality, online learning, memory constraints, streaming data where new categories appear frequently

Interview tip: When discussing a recommendation system, mention that you would use learned embeddings for user and item IDs. This shows you understand modern approaches to high-cardinality categorical features.

Feature Crosses and Interaction Features

Sometimes the relationship between features matters more than the features themselves.

Feature cross: Combine two or more features to create a new feature. Example: city x device_type creates features like New_York_mobile and London_desktop.

Why feature crosses matter:

Linear models cannot learn interactions without them

They encode domain knowledge (the effect of time-of-day on click rate differs by country)

They can dramatically improve model performance

Examples of useful crosses:

day_of_week x hour_of_day -- Captures weekly patterns (Sunday morning vs. Wednesday afternoon have very different user behaviors)

user_age_bucket x content_category -- Different age groups prefer different content

device_type x country -- Mobile usage patterns vary significantly by region

query_intent x result_type -- Navigational queries need website results, informational queries need articles

user_subscription_tier x price_bucket -- Premium users respond differently to price signals

previous_purchase_category x current_browse_category -- Cross-sell opportunities

Tree-based models and neural networks can learn some interactions automatically, but explicit crosses still help, especially for important known interactions. At Google, the Wide and Deep model explicitly uses feature crosses in the wide component because they memorize specific feature combinations that the deep network might miss.

Automated Feature Interaction Discovery

For large feature spaces, manually identifying all useful crosses is impractical. Several approaches help:

AutoML feature interaction search: Tools like Featuretools or Google AutoML Tables automatically generate and evaluate feature crosses.

Gradient boosted tree feature importance: Train a GBDT model and examine which feature pairs co-occur in tree splits. This reveals useful interactions.

Neural network attention weights: In deep models, attention mechanisms naturally learn which features to combine.

Feature Selection Methods

Not all features are useful. Including irrelevant or redundant features can hurt model performance (overfitting, increased latency) and increase complexity. Feature selection identifies the most valuable subset.

Filter Methods

Evaluate features independently of the model using statistical measures:

| Method | How It Works | Feature Types | Pros/Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | Pearson/Spearman correlation with target | Numerical | Fast, but only captures linear relationships |

| Mutual Information | Measures statistical dependence between feature and target | Any | Captures non-linear relationships, but expensive for large datasets |

| Chi-squared test | Tests independence between categorical feature and target | Categorical | Simple hypothesis test, only for categorical features |

| ANOVA F-test | Tests if means differ across target classes | Numerical features, categorical target | Fast, assumes normality |

| Variance threshold | Remove features with near-zero variance | Any | Very fast, catches constant or near-constant features |

Wrapper Methods

Use the model itself to evaluate feature subsets:

Forward selection: Start with no features, add the one that improves performance the most. Repeat until adding features stops helping. Good for small feature sets but expensive for large ones.

Backward elimination: Start with all features, remove the one whose removal hurts performance the least. Repeat. Similar cost to forward selection.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE): Train model, remove least important features, retrain. Repeat until desired number of features reached. Works well with models that provide feature importance (linear models, random forests).

Embedded Methods

Feature selection happens during model training:

L1 regularization (Lasso): Drives feature weights to exactly zero, automatically selecting features. The regularization strength controls how many features are removed.

Tree-based feature importance: Random forests and gradient boosted trees provide feature importance scores based on how much each feature contributes to reducing loss. Use mean decrease in impurity or permutation importance.

Attention weights: In transformer models, attention scores indicate which features the model focuses on.

Interview tip: In an interview, mention that you would start with all reasonable features, use tree-based feature importance to identify the top contributors, and then verify by removing low-importance features and confirming model performance does not degrade.

Training-Serving Skew

This is one of the most important and most overlooked topics in ML system design. Training-serving skew occurs when the features available during training differ from what is available at serving time.

Common Causes

Feature leakage: Using information at training time that would not be available at prediction time. Example: using number of future purchases to predict whether a user will make a purchase. This is the most dangerous type because it inflates offline metrics dramatically but the model fails in production.

Temporal leakage: Using future data to predict past events. Example: computing a user average rating using all their ratings, including ones that have not happened yet at prediction time. Another common example: using the label itself as a feature (accidentally including was_fraudulent as an input feature to the fraud model).

Feature computation differences: Features computed differently in batch (training) vs real-time (serving). Example: training with exact 30-day averages from a data warehouse (computed via SQL over complete data), but serving with approximate real-time aggregates (computed via streaming counter with potential delays). Even small differences can cause significant model degradation.

Data freshness gaps: Training features computed from yesterday data, but serving features are hours or minutes old. For time-sensitive features like trending topics or stock prices, this gap matters.

Data processing bugs: Different code paths for training and serving feature computation. A common example: training pipeline handles null values by imputing with zero, but serving pipeline imputes with -1.

How to Prevent It

Use the same feature computation code for training and serving (feature stores are designed exactly for this)

Point-in-time correct joins -- when constructing training data, only use features that would have been available at the time of prediction. This means joining with feature snapshots, not current values.

Log features at prediction time -- store the exact features used for each prediction, then use those logged features for training. This guarantees zero training-serving skew but requires more storage.

Monitor feature distributions -- compare training feature distributions to serving feature distributions. Alert if KL divergence or PSI exceeds a threshold.

Integration tests -- write tests that compute features both ways (training path and serving path) for the same input and assert they match.

Interview tip: Mentioning training-serving skew unprompted is a strong signal of production experience. Most textbooks do not cover it, so knowing about it signals you have worked on real systems.

Privacy Considerations

ML systems often deal with sensitive user data. In interviews at large tech companies, showing awareness of privacy is increasingly important.

PII (Personally Identifiable Information)

Data that can identify a specific person: name, email, phone number, address, SSN. ML models should rarely use raw PII as features. Instead, hash or tokenize identifiers and use aggregated features derived from the data.

Anonymization Techniques

Hashing: Replace identifiers with hash values. One-way but vulnerable to re-identification through rainbow table attacks. Use salted hashes for better security.

K-anonymity: Ensure each record is indistinguishable from at least K-1 other records on quasi-identifiers (age, zip code, gender). Prevents singling out individuals.

L-diversity: Extension of k-anonymity that ensures each equivalence class has at least L distinct values for sensitive attributes.

Data masking: Replace sensitive values with realistic but fake values. Useful for development and testing environments.

Differential Privacy

Add calibrated noise to data or model outputs so that no individual data point significantly affects the result. Used by Apple (for emoji usage analytics, Safari suggestions) and Google (for Chrome usage statistics via RAPPOR).

Key idea: The output of an analysis should be roughly the same whether or not any single individual data is included. Formally, for any two datasets differing by one record, the probability of any output should differ by at most a multiplicative factor of e^epsilon.

Epsilon (privacy budget): Controls the privacy-accuracy trade-off. Smaller epsilon = more privacy but more noise. Typical values: epsilon between 1 and 10 for reasonable utility.

Local differential privacy: Add noise on the client side before data leaves the device. Strongest privacy guarantee because the server never sees raw data. Used by Apple.

Global (central) differential privacy: Add noise at the server after aggregation. Better accuracy for the same privacy level, but requires trusting the server.

DP-SGD (Differentially Private Stochastic Gradient Descent): Clip individual gradients and add Gaussian noise during training. Allows training ML models with formal privacy guarantees. The trade-off is reduced model accuracy -- typically 2-5 percent drop depending on privacy budget.

Federated Learning

Train ML models without centralizing data. Each device trains a local model on its data and sends only model updates (gradients) to the server.

Used by: Google (Gboard keyboard predictions -- next-word prediction trained across millions of Android devices), Apple (Siri improvements, QuickType keyboard, Hey Siri detection)

How it works in practice:

Server sends current global model to selected devices

Each device trains locally on its data for a few epochs

Devices send model updates (gradients or weight deltas) to server

Server aggregates updates using Federated Averaging (FedAvg) -- weighted average of client updates

Updated global model is sent back to devices

Repeat

Benefits: Data stays on device (improved privacy), reduces data transfer, leverages diverse data

Challenges: Communication overhead (model updates can be large -- use compression), non-i.i.d. data across devices (each user has different data distribution, causing training instability), model aggregation complexity, cannot inspect training data for debugging, straggler devices slow down training rounds

Secure Aggregation: Cryptographic technique ensuring the server can only see the aggregate update, not individual device contributions. Adds computational overhead but strengthens privacy guarantees.

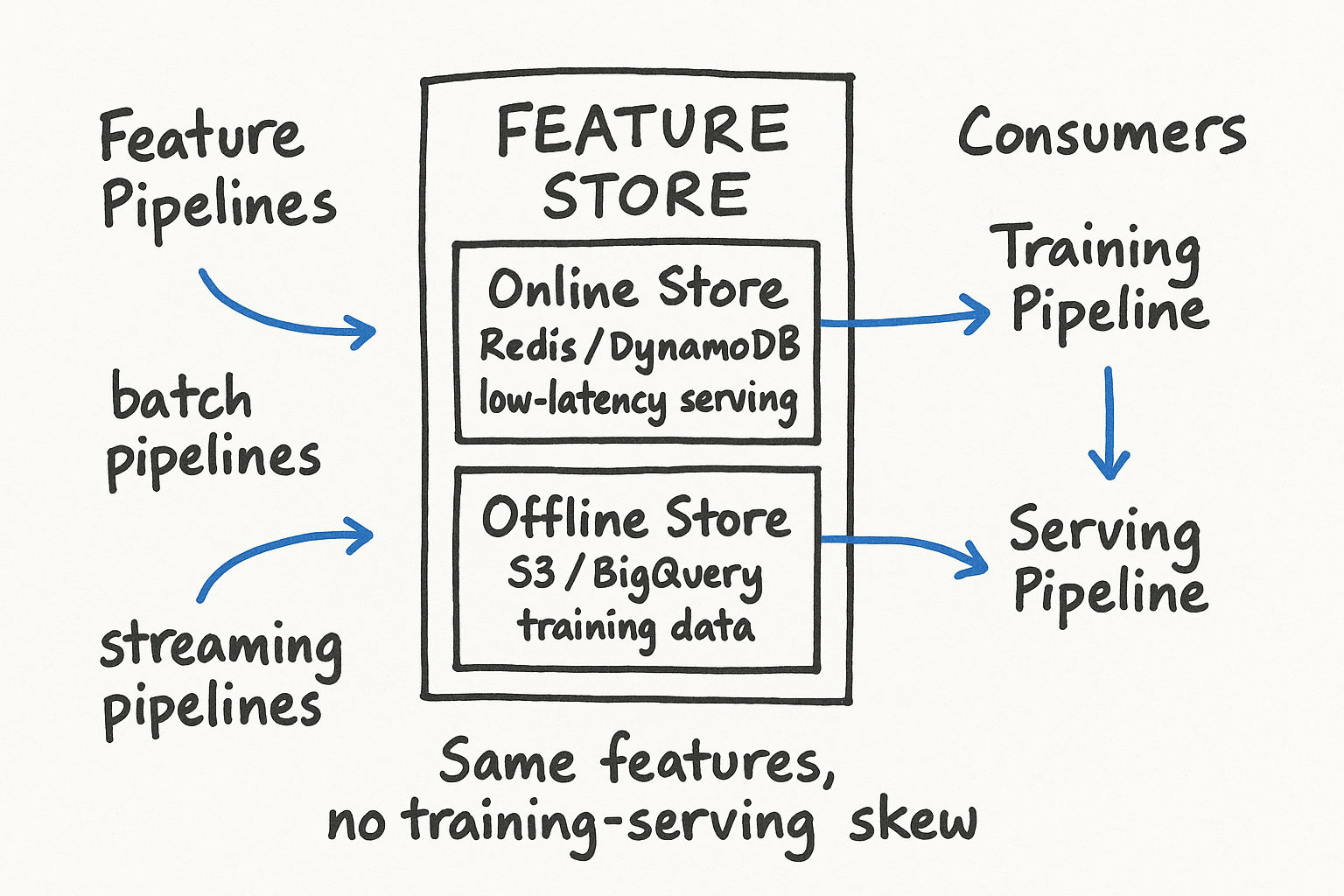

Feature Stores

A feature store is an infrastructure component that manages the storage, computation, and serving of ML features. Think of it as a specialized database optimized for ML workflows.

Why Feature Stores Matter

Without a feature store:

Each ML team computes features independently -- duplicated work

Training features and serving features are computed differently -- training-serving skew

Features are scattered across notebooks, scripts, and pipelines -- no reuse

Feature freshness varies and is hard to track -- stale features

No governance over who uses what features -- compliance risk

With a feature store:

Single source of truth for feature definitions and data

Consistent features across training and serving

Feature reuse across teams and models

Point-in-time correctness for historical training data

Low-latency serving for real-time features

Feature governance with lineage tracking and access controls

Feature Store Architecture

A feature store typically has two storage layers:

Offline store: Stores historical feature values for training data construction. Backed by a data warehouse or object storage (S3, GCS). Supports batch reads with point-in-time joins. When you construct training data, you query the offline store for feature values as they existed at the time each training example was generated.

Online store: Stores the latest feature values for real-time serving. Backed by a low-latency key-value store (Redis, DynamoDB, Bigtable). Supports single-digit millisecond reads. When a prediction request comes in, the serving layer fetches current feature values from the online store.

Feature computation engine: Transforms raw data into features. Can run batch transformations (Spark jobs computing daily aggregates) and streaming transformations (Flink or Spark Streaming computing real-time features like count of actions in the last 5 minutes).

Popular Feature Stores

| Feature Store | Type | Key Strengths | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feast | Open source | Simple, Kubernetes-native, good community | Teams starting out, cloud-agnostic deployments |

| Tecton | Managed (commercial) | Real-time features, enterprise support, built by Feast founders | Production systems needing streaming features |

| Hopsworks | Open source + managed | Full ML platform, great Python API | Teams wanting an integrated ML platform |

| Amazon SageMaker Feature Store | Managed (AWS) | Tight AWS integration | AWS-native teams |

| Google Vertex AI Feature Store | Managed (GCP) | Tight GCP integration, BigQuery support | GCP-native teams |

| Databricks Feature Store | Managed | Tight Spark integration, Unity Catalog | Databricks users |

How Feature Stores Solve Training-Serving Skew

The core architecture ensures consistency:

Feature definition code is written once and registered in the feature store

The same transformation logic runs for both offline (batch for training) and online (real-time for serving)

Point-in-time joins in the offline store ensure training data uses features as they existed at prediction time, not current values

Monitoring tracks feature distributions across training and serving, alerting on divergence

At Uber, their Michelangelo platform (which includes a feature store) reduced training-serving skew incidents by over 90 percent after adoption. Features like trip_count_last_7_days are computed once in the feature store and served consistently to both training pipelines and the real-time prediction service.

Interview tip: When discussing any production ML system with real-time features, mention a feature store. Say something like: I would use a feature store like Feast or Tecton to ensure consistent feature computation between training and serving, with the offline store backed by our data warehouse for training data construction and an online store backed by Redis for sub-10ms feature retrieval at serving time.

Putting It All Together: A Feature Engineering Checklist

When you are in an ML system design interview, use this mental checklist for the data and features portion:

Identify data sources -- Where does the training data come from? What event logs, databases, and third-party sources are available?

Define the label -- How do you get ground truth? Is it natural (user clicks), human-annotated, or programmatic?

List feature categories -- User, item, context, interaction features. Be specific about 5-10 concrete features.

Handle missing values -- Strategy per feature based on missingness rate. Median plus missing indicator for numerical, separate category for categorical.

Apply appropriate encoding -- One-hot for low cardinality, embeddings for high cardinality, target encoding for medium cardinality with strong target correlation.

Scale if needed -- Standardize for neural nets, log-transform skewed features, skip for tree models.

Create feature crosses -- For known important interactions. User segment x item category, time x location.

Select features -- Use feature importance from a baseline model to identify and remove low-value features.

Address training-serving skew -- Same computation path for train and serve. Consider logging features at prediction time.

Consider privacy -- Anonymize PII, evaluate differential privacy needs, mention federated learning if on-device.

Mention feature store -- For production systems with real-time features.

Key Takeaways

Feature engineering matters more than model selection in most production ML systems

Know the standard techniques: scaling, encoding, imputation, binning, feature crosses

Different domains (ads, recommendations, fraud, search) have different feature engineering patterns -- know the common features for your interview company

Feature selection (filter, wrapper, embedded methods) prevents overfitting and reduces serving latency

Training-serving skew is one of the most common causes of ML system failures in production

Feature stores solve the consistency and reuse problem for ML features at scale

Privacy awareness (PII handling, differential privacy, federated learning) is increasingly expected in interviews

Always match your technique to the data type and downstream model: tree models need less preprocessing, neural networks benefit from careful scaling and encoding